Helen Phillips Biography

Early life and the Beginnings

1931 – 1936

Helen Elizabeth Phillips was born in Fresno in 1913. She came from a family descending from the first german settlers on the West Coast. Her father was a violin teacher and the other members of her family were artistically and intellectually inclined: her sister Ruth became an art gallerist and her other sister an anthropologist.

From about the age of thirteen, Phillips knew she wanted to be a sculptor, always finding ways to carve; she would use wood, soap, or even lumps of dry earth she found in vineyards during the dry season. By fifteen, while living with her family in San Francisco, she took a summer sculpture class at the California School of Fine Arts (now the San Francisco Art Institute).

After high school, she returned to study with sculptors Ralph Stackpole and Gottardo Piazzoni from 1932 to 1935.

During this time, she met Diego Rivera, a close friend of Stackpole, who had recently completed commissions for the San Francisco Stock Exchange and the California School of Fine Arts. It was not Rivera’s masterful mural painting that most impressed Phillips, but his renowned collection of pre-Columbian artifacts and Mexican sculptures. These, along with the University Museum’s collection of Indigenous American, Chinese, and Aztec arts and her growing interest in the poetry of the early Surrealist writers, and in their psychoanalytic techniques shaped Phillips’s sculptural ideals.

Paris and Atelier 17

1936 – 1939

In 1936, after winning the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art Purchase Prize for her sculpture Young Woman (1935–36) and completing a private sculpture commission for Saint Joseph Catholic Church in Sacramento, CA, she was awarded a Phelan Traveling Fellowship to study abroad.

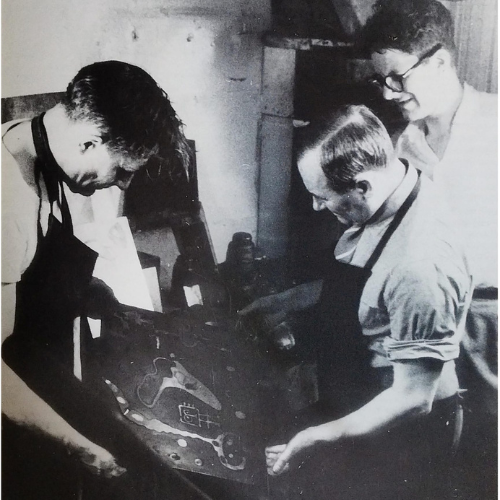

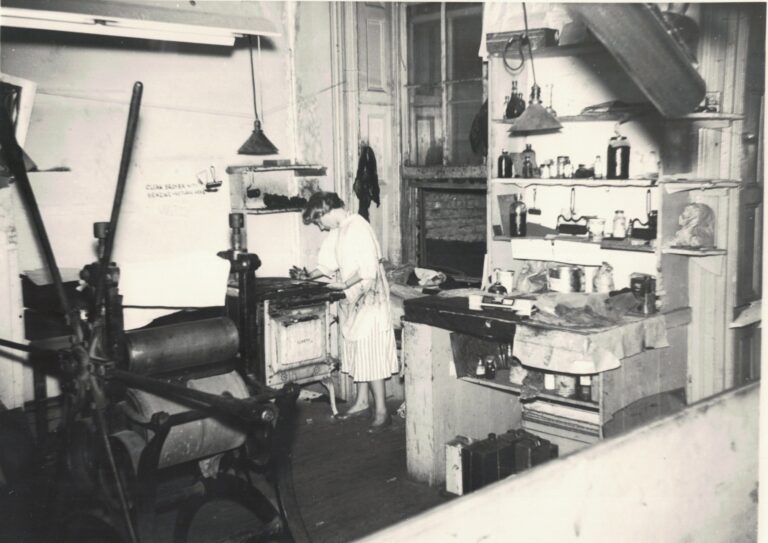

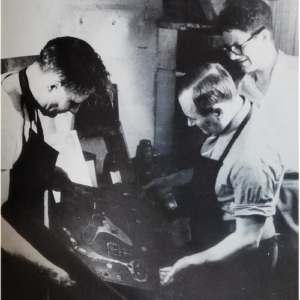

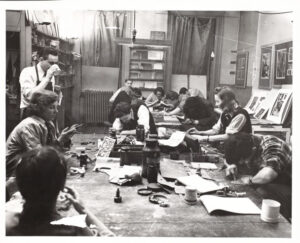

She traveled throughout Austria, Germany, Italy, and France, eventually settling down in Paris to a little room on the Impasse de Rouet. Soon carving sculptures outdoors became impracticable because of the dropping temperatures. She instead joined friends at Atelier 17, the intaglio print workshop of the renowned English artist Stanley William Hayter, whom she would later marry.

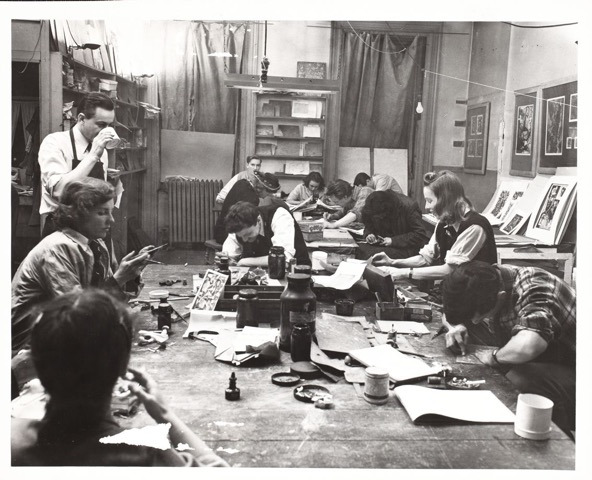

A hub of avant-garde experimentation, the atelier transcended generational and stylistic divisions, gathering together artists who subsequently endorsed different movements. Among its attendees were Pablo Picasso, Max Ernst, Alberto Giacometti, Joan Miró, André Masson, Jean Hélion, Maria Helena Vieira da Silva, Gabor Peterdi, and Nina Negri, to name a few.

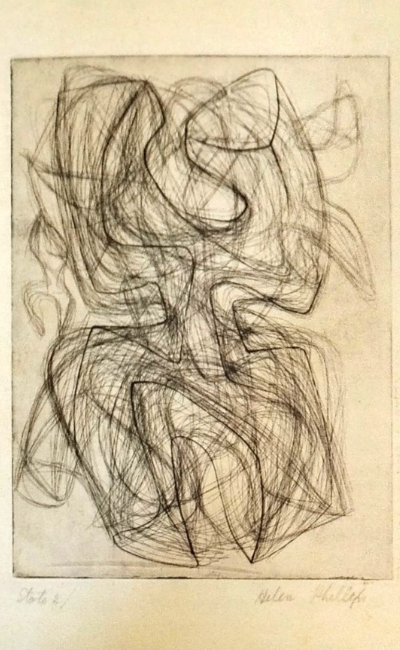

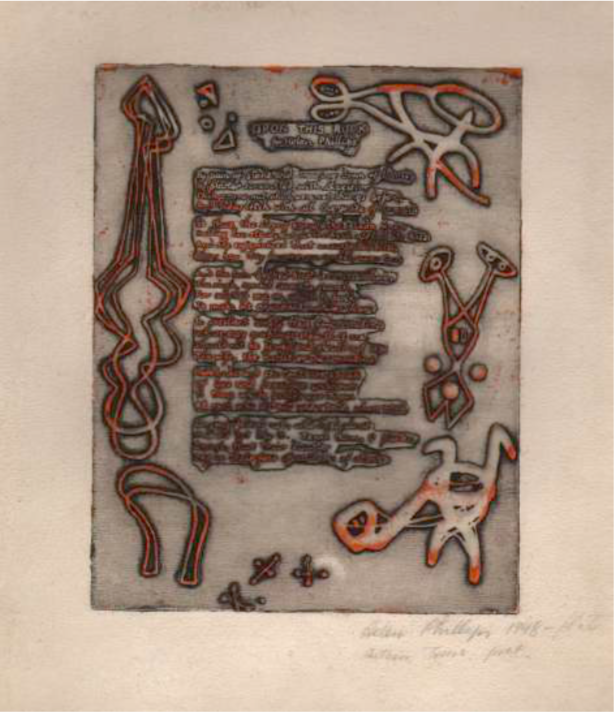

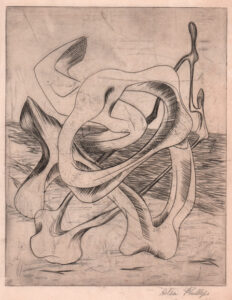

In those early Parisian years, she produced approximately thirty-five copper plates, almost all representing images inspired by the Surrealist practice of “automatic writing”, aimed at freeing the unconscious. Driven by her interest in pure form, she sought to achieve what she later called the ambiguous poetic image, combining abstract content with the ambiguity of Surrealist concepts.

London and the World War II

1939 – 1940

As the political situation worsened in Europe and another war seemed imminent, Phillips and Hayter, who had been openly living together since 1937, left for London in 1939, as Hayter was called to serve his country.

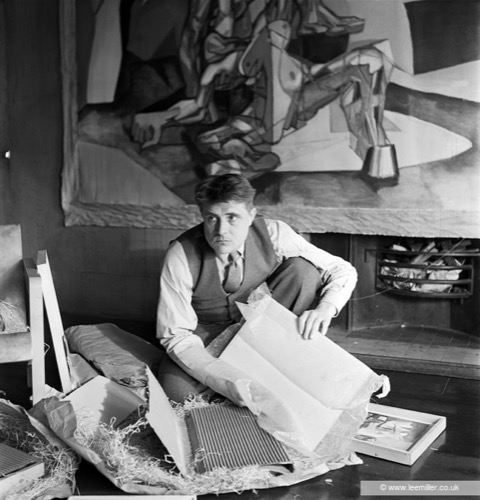

Due to Hayter’s political stance and commitment (he had produced two portfolios in aid of the Spanish Republic and housed Spanish refugees), there was an urgency for the couple to flee France before German forces invaded. Both artists were forced to abandon most of their works in Paris. Later, Peggy Guggenheim was able to retrieve some of their work (including Hayter’s important painting Parturition, 1939), but most Phillips’s sculptures were lost and, so far, none has been recovered.

The couple began working with Roland Penrose, Ernö Goldfinger, and Julian Trevelyan in the Industrial Camouflage Research Unit, where artists helped civilian businesses and factories use camouflage to defend themselves against air raids.The Unit, based in Goldfinger’s offices, consisted of leading figures in the English Surrealist Group. During these nerve-racking months, Phillips kept sculpting any way she could, while also making prints at Julian Trevelyan’s studio at Durham Wharf. Apart from Trevelyan, Hayter and Phillips’s close circle of friends included John Buckland-Wright, Anthony Gross, Lee Miller, and Roland Penrose. During this time Phillips became close to Ërno and Ursula Goldfinger. In 1940, the Industrial Camouflage Research Unit, having been dismantled, Phillips and Hayter decided to leave Europe for the United States.

The New York Years

1940 – 1950

Due to immigration issues, Hayter left in an Allied convoy from Liverpool to a Canadian port, arriving in NewYork via train. Phillips, then pregnant with their first son, left England on one of the last American refugee boats for New York.

They stayed for a week with Gordon Onslow Ford before leaving for San Francisco, where Hayter had a summer teaching position lined up at the California School of Fine Arts. On their way to California, Phillips and Hayter were married in Reno, Nevada. Their first child was born at the end of August, seven weeks prematurely. Once the summer session was over, Hayter returned to New York, where he had been invited to teach and reestablish his Atelier 17 at the New School for Social Research. Phillips joined him with their infant son at the beginning of December. They moved into a two-bedroom apartment on 14th Street and Seventh Avenue. It was spacious, but still did not have enough room for them to work. Due to Augy’s health issues, they left New York and spent the first two years on the East Coast in Connecticut. They then moved to New York City, from where Hayter would continue to commute.

“This proved nearly disastrous for us, both morally and financially, because of the isolation from our kind of people, which was essential for our lifestyle.” (from Phillips’s unpublished papers)

By early1943, they went back to New York, first to Perry Street, then to Waverly Place. Having moved constantly since leaving Paris, there they found for the next four years the stability they needed. Despite being overwhelmed with work and responsibilities, their strong constitutions made these years prolific and vital for both artists, crucial for their aesthetics.

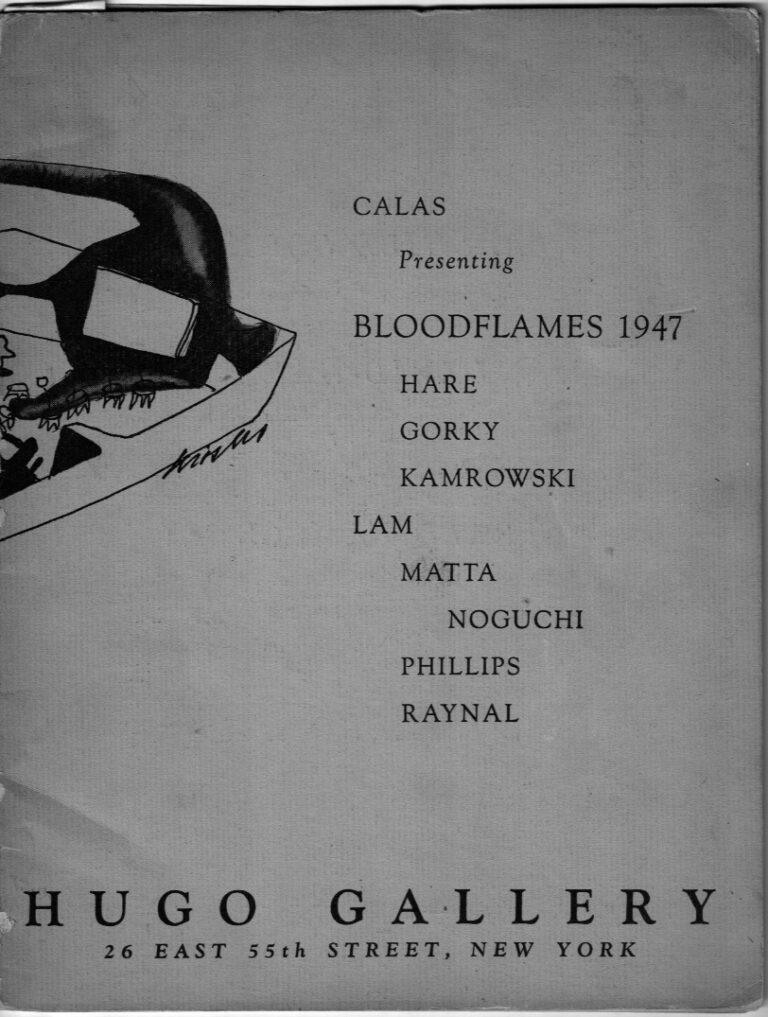

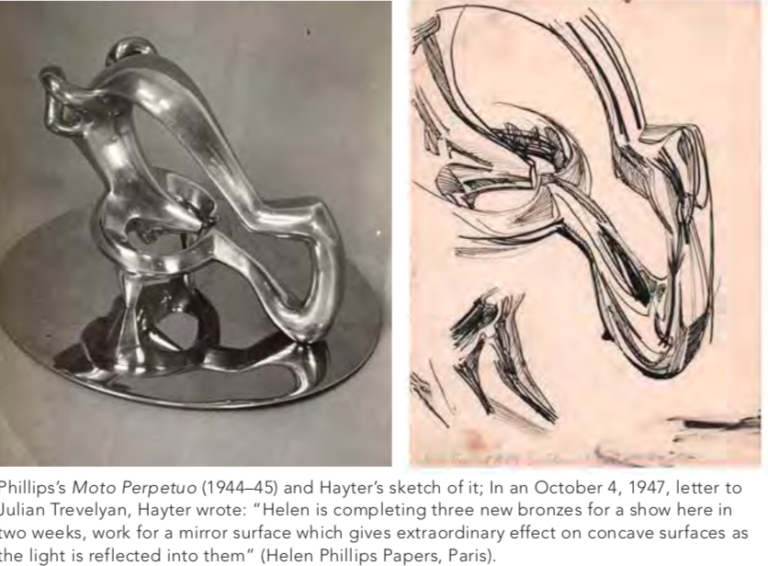

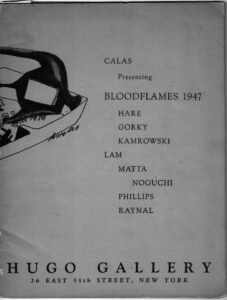

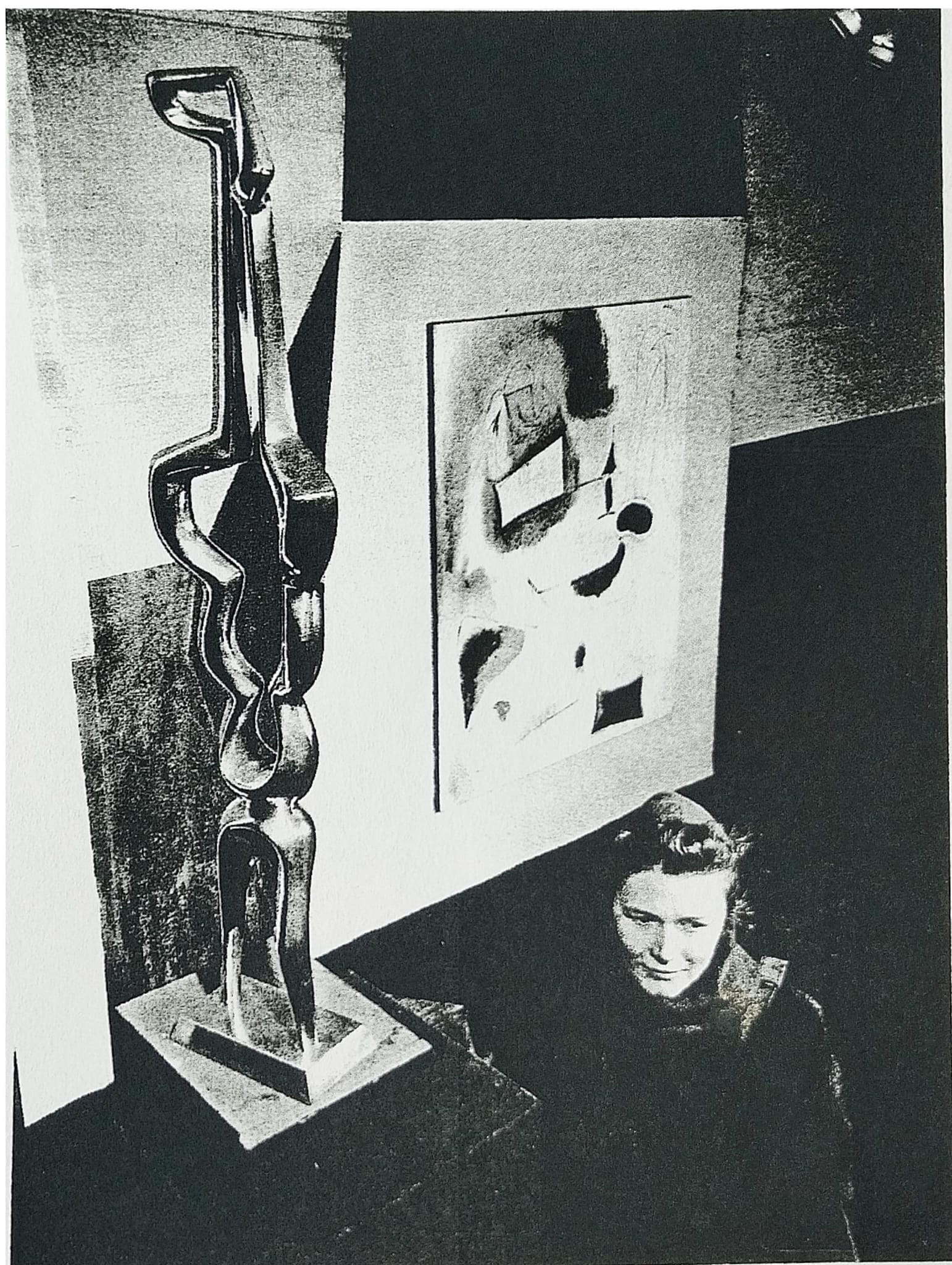

Within just a few years of arriving in New York, Phillips made a name for herself; her reputation as a sculpture set her on par with the leading Surrealist and Abstract Expressionists of the time. Besides being published in the prestigious avant-garde art magazine Tiger’s Eye, her work was included in many significant exhibitions. In 1941, her hieratic sculpture Inverted Head (1941) was included in Surrealism, an exhibition organized by Roberto Matta at the New School for Social Research. In 1945, she displayed her carved limestone sculpture Genetrix (1943) in the second Women exhibition at Peggy Guggenheim’s Art of This Century Gallery. In 1947 she was represented by her sculptures Moto Perpetuo and Dualism (both 1944–45) in the landmark exhibition Bloodflames, curated by Nicholas Calas, at New York’s Hugo Gallery. Included in the exhibition were some of the most significant representatives of Surrealism and Abstract Expressionism: Isamu Noguchi, Roberto Matta, David Hare, Wilfredo Lam, Arshile Gorky, and Jeanne Reynal.

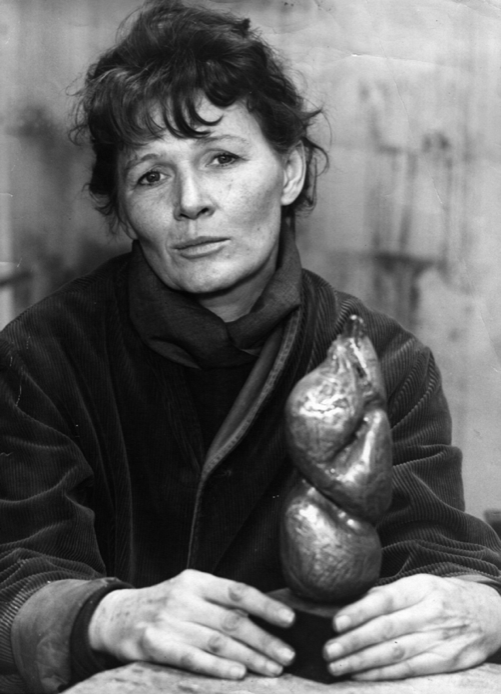

By this time, Phillips was creating medium-sized sculptures expanding her range of techniques and materials, which included bronze (which she polished herself), stone, balsa wood, plaster, iron, and aluminum wire tubes. Most of these works reflected her personal surrealist vocabulary of abstract forms.

When Phillips and Hayter moved into the brownstone on Waverly Place, in 1944, they could finally afford the space for their professional, social, and family needs. Phillips settled her sculpture studio in the old dining room at the front of the building and began again to cut stone in the backyard, while Hayter used an upstairs room for his painting and drawing. The large kitchen became a frequent gathering place for their friends—among them Marc Chagall, Jacques Lipchitz, André Masson, and Joan Miró—to exchange ideas about art.

In 1949 Phillips and Hayter were featured in Sidney Janis’s 1949 exhibition Artists: Man and Wife, which paired artist couples: Elaine and Willem de Kooning, Lee Krasner and Jackson Pollock, Barbara Hepworth and Ben Nicholson, and Sophie Taeuber-Arp and Jean Arp. Clement Greenberg’s assessment of the show offered qualified praise for Phillips at the expense of the other women artists represented:“Helen Phillips was the only woman whose work equaled that of the man.” Interestingly, the backwards compliment reflects the broader critical perception of the time that women artists were in a subordinate position to men.

Phillips, Atelier 17 and the “Surrealists in Exile”

By then mother of two young children, Phillips could rarely go to Atelier 17 and work on her prints.

She later remembered that when she did, she would place her second child Julian’s cradle under the press for protection. However, she was “intimately involved with all that was going on at the Atelier through Bill (as Hayter was called) and the artists who would come by their house.”

In several recorded interviews and unpublished writings, Phillips provided a detailed account of her lifestyle with Hayter, their means of production at the time, and of her household, where many “Europeans in exile” and American artists would gather to discuss what would later become history.

“Until we moved to Waverly Place, I could only note ideas in small plasters and engrave a few plates on the fringe of Bill’s workspace and domestic demands. Finally at Waverly Place I could begin to cut stone again in the outdoor yard. From my study on the basement ground I could at the same time keep an eye on our small children, who were fed, bathed and put to bed by seven, leaving me free, after supper, to concentrate on my work…and Bill could could go to the shop until midnight for classes or projects he was on and go to a pub with his crowd afterwards at the Cedar Tree or the White Horse Tavern…it was in the dining room off the very big kitchen which also housed Julian’s playpen, a sofa, a very big dining table and chairs around, that our personal friends and particularly our house guests… gathered for a coffee and art-idea discussions. This room was the hub of our household. Beside Ruthven (Todd) I particularly remember Chagall, who, badly grieving for his wife’s death, found consolation there, Lipchitz, Masson, Becker, Miró on very frequent occasions…People coming to our front door were taken directly to the top floor, to Bill’s studio or down to the kitchen, en famille…”

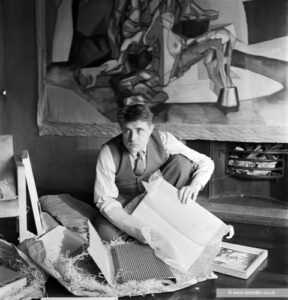

Helen Phillips and S.W. Hayter: an artistic complicity

“There is a fourth dimension to the marriage of working artists…there is marriage…you have children, and when your professions are the same, and you understand so much of so much, it gives another dimension to the marriage. Some people see it as a negative but there is a very very positive side to it…”

By the late 1940s, Phillips and Hayter had managed to buy a brownstone house on Washington Street in the West Village, where they shared a large atelier in the basement. By then, they had developed a deep artistic bond, sharing interests, a vision, and exploring new directions in their art.

Phillips recalls their enthusiasm in discussing Thompson Darcy’s theories of modular growth and how they relied on each other’s judgment to advance when their work stalled. Their mutual understanding was intuitive; they instantly grasped where the other’s work was headed. Coming from different artistic backgrounds, their insights into each other’s work were unconditioned, and had a complementary quality that benefited both. Phillips’s admiration for Hayter never faltered, and Hayter constantly supported her art. He always included her prints in his Atelier 17 exhibitions, illustrated them in his books, and often sketched from her works.

By 1949, Phillips’ work had gained such prominence within the circle of leading American avant-garde sculptors that she was invited to join the prestigious Eighth Street Club. Its members included Mark Rothko, Robert Motherwell, William Baziotes, Isamu Noguchi, and David Hare.

However, she reluctantly had to decline this prestigious offer as Hayter was adamant about returning to Paris for a couple of years. Those two years turned eventually into an indefinite period.

Later, in an interview with David Cohen, Phillips admitted she regretted returning to Paris.

“For some reason Bill [Hayter] wouldn’t play with it at all. I never understood it. It would have made a great difference to me because that group (the Eight Street Club) supported me, morally, as a sculptor.”

Return to Paris

The 1950s through 1970s

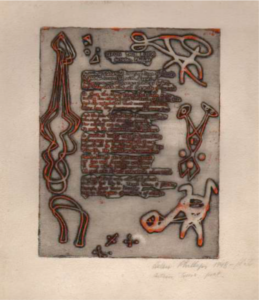

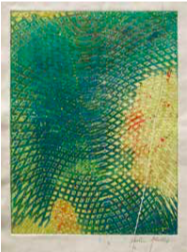

In the early summer of 1950, after the Hayters returned to France, Phillips was invited by André Chanson, director of the Petit Palais, to showcase fourteen sculptures in the exhibition New York Six, and thereafter was invited to exhibit in numerous European international Biennials and Salons. In the late fall of 1950 Hayter reopened Atelier 17 and Helen started to frequent it again. Over the following four years, abandoning her black and white engravings, she developed her own method of making bold colour prints, using deep bite and simultaneous colour printing.

In the 1950s the French poet André Lothe, called for artists and intellectuals to settle in the houses and ruins of Alba-la-Romaine, an idyllic medieval town in the Ardèche region of southern France. Lothe’s article, which appeared in the Parisian newspaper Combat, made the rounds in the cafés of Montparnasse, and many artists of the Paris School decided to leave the postwar struggles of the city for the charm and serenity of Alba. Artists of all nationalities purchased and settled in about thirty houses there, establishing an international art scene in an otherwise quiet, provincial town. Phillips and Hayter were among those who joined this artists’ community: in 1953 the couple purchased an old stone house where they had adjoining studios. They would spend most of their summers there with their children, finding fulfillment and inspiration in nature and a simpler way of life.

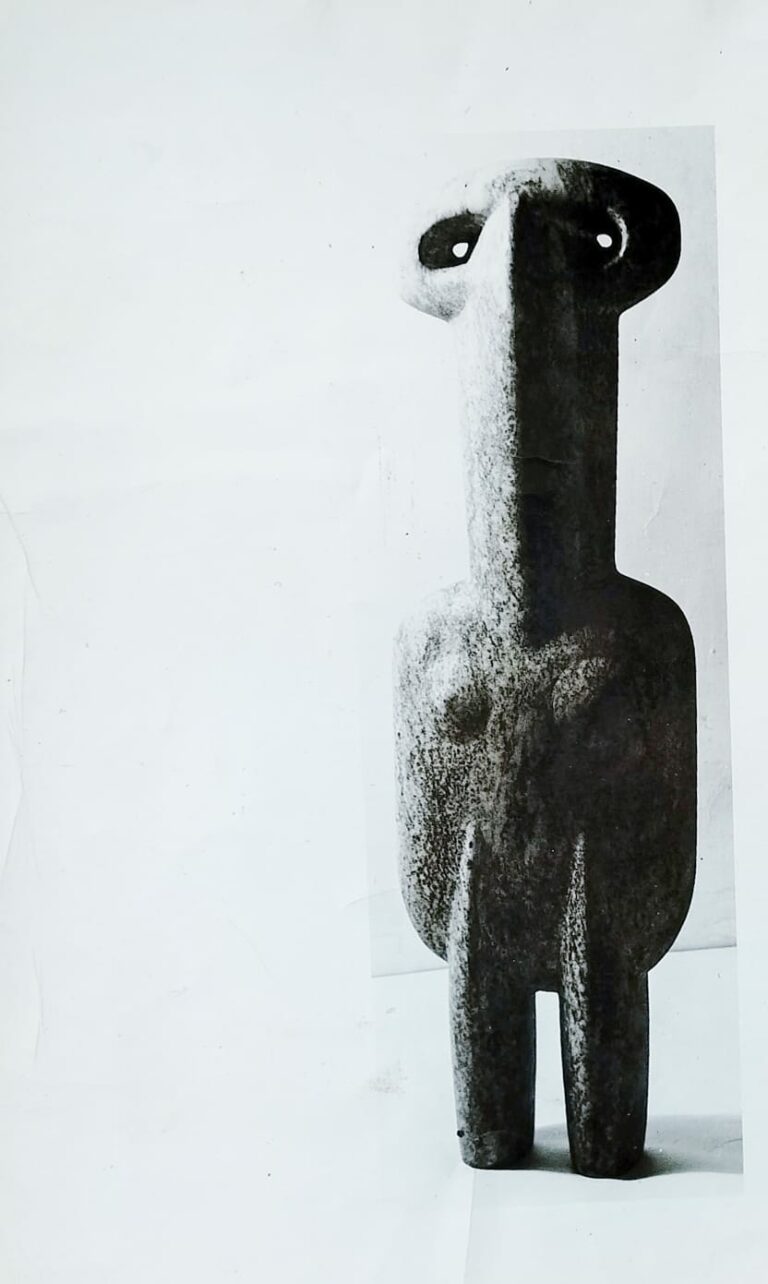

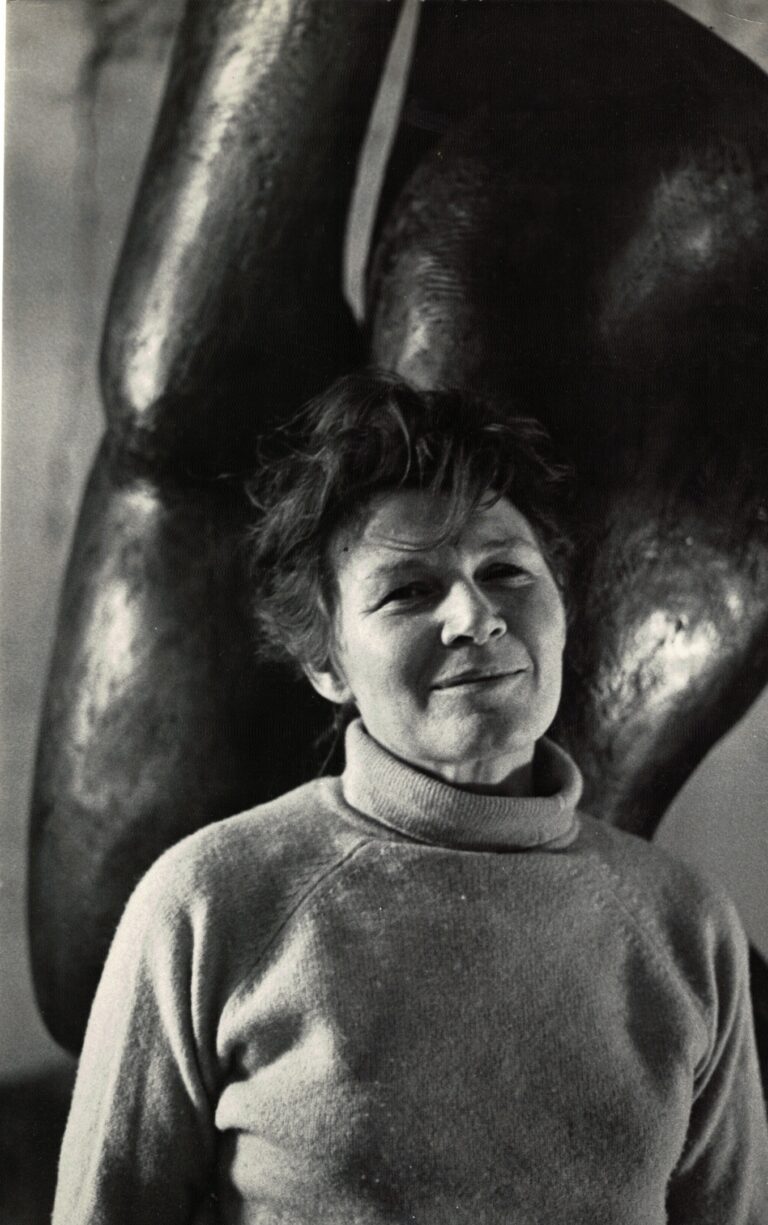

In Alba, Phillips began carving 300–400 year old oak trees found nearby and created multiple large-scale totems, one titled Family Totem (1953), reaching a height of seventeen feet. She continued to work in her ambiguous poetic image style, which was strongly influenced by her interest in ethnographic arts, merging human forms with the natural world. A pair of totem-like figures titled Eve (1958) and Adam (1960) were purchased by the Dallas Museum of Art in 1960.

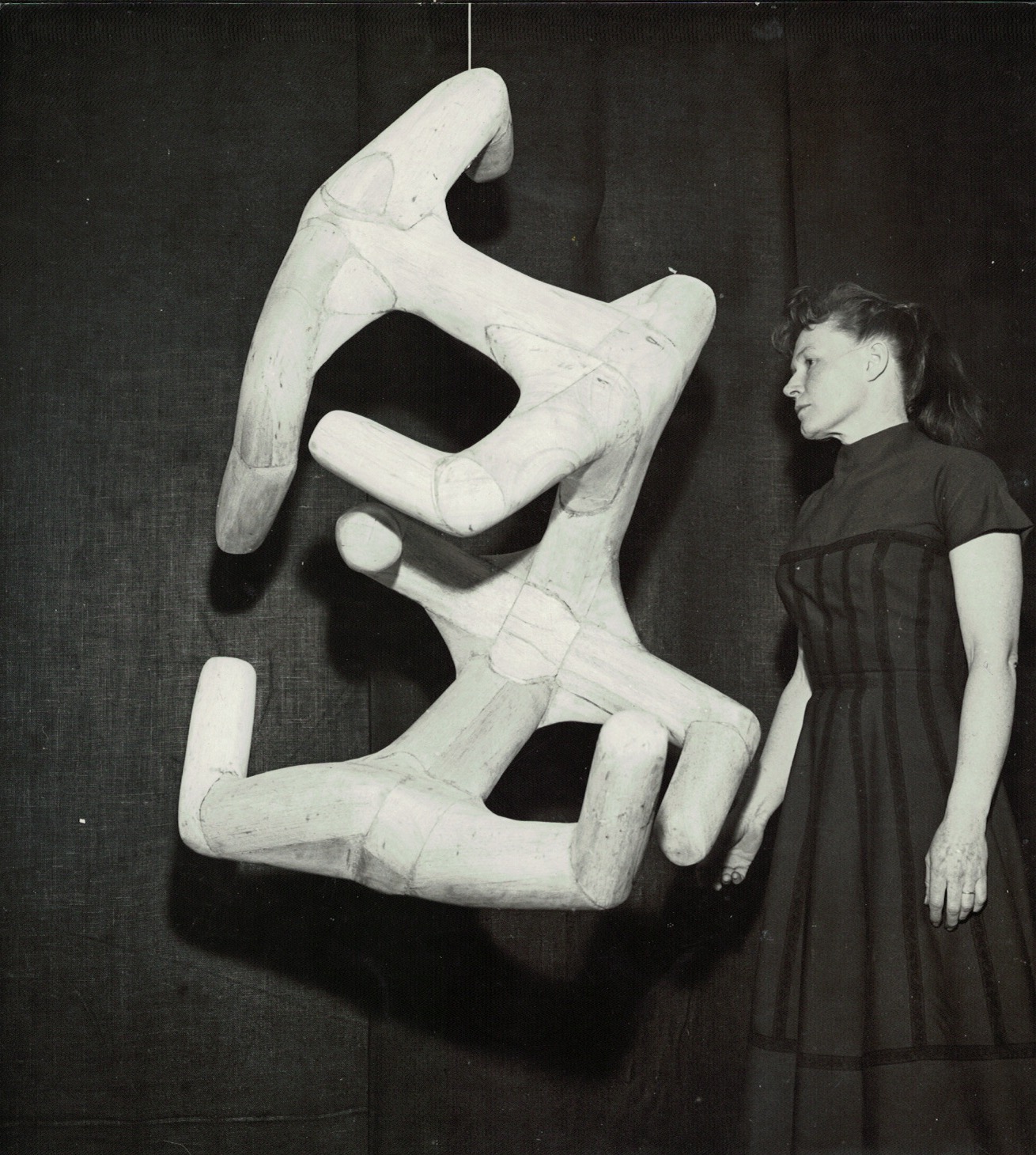

In 1956, at Ërno Goldfinger’s invitation, Phillips participated in the breakthrough exhibition This Is Tomorrow at the Whitechapel Gallery in London, with a hanging sculpture carved from balsa wood titled Suspended Figure (1956). The original piece, purchased by Goldfinger, is now lost, but a cast in aluminum survives in the Goldfinger residence, at 2 Willow Road in London, with a photographic documentation of the artist posing next to the original. Goldfinger noted in a letter to Victor Pasmore (17 July1956) that “Helen Phillips stayed with me for some 10 days and finished her piece of sculpture at my house…it is in balsa wood and I think rather good…She made a most hellish dust over the whole house when sandpapering it; everything is covered with a thin layer of balsa dust!”

Many of Phillips’s sculptures from this time were exhibited in Paris at the Musée Rodin, Salon de Mai, Galerie Pierre, Galerie La Hune, Galerie Claude Bernard, and consistently throughout Europe where she was often called to represent the United States. In 1962 she took part in the exhibition, 14 Americans in France, which, initiated by the American Cultural Center in Paris, travelled all over the United States.

A Module of Growth

“It was not until 1954 when I read D’Arcy Thompson’s inspiring volumes on growth and form that I evolved a geometric unit to express three-dimensional movement which in repetition, produced a seemingly endless variety of forms, column spirals in geometric relationship and developed from a single given length: A Module of Growth.”

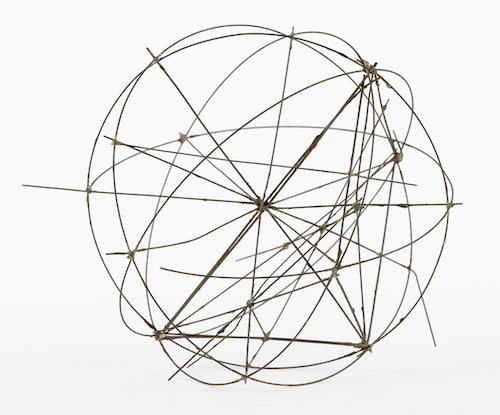

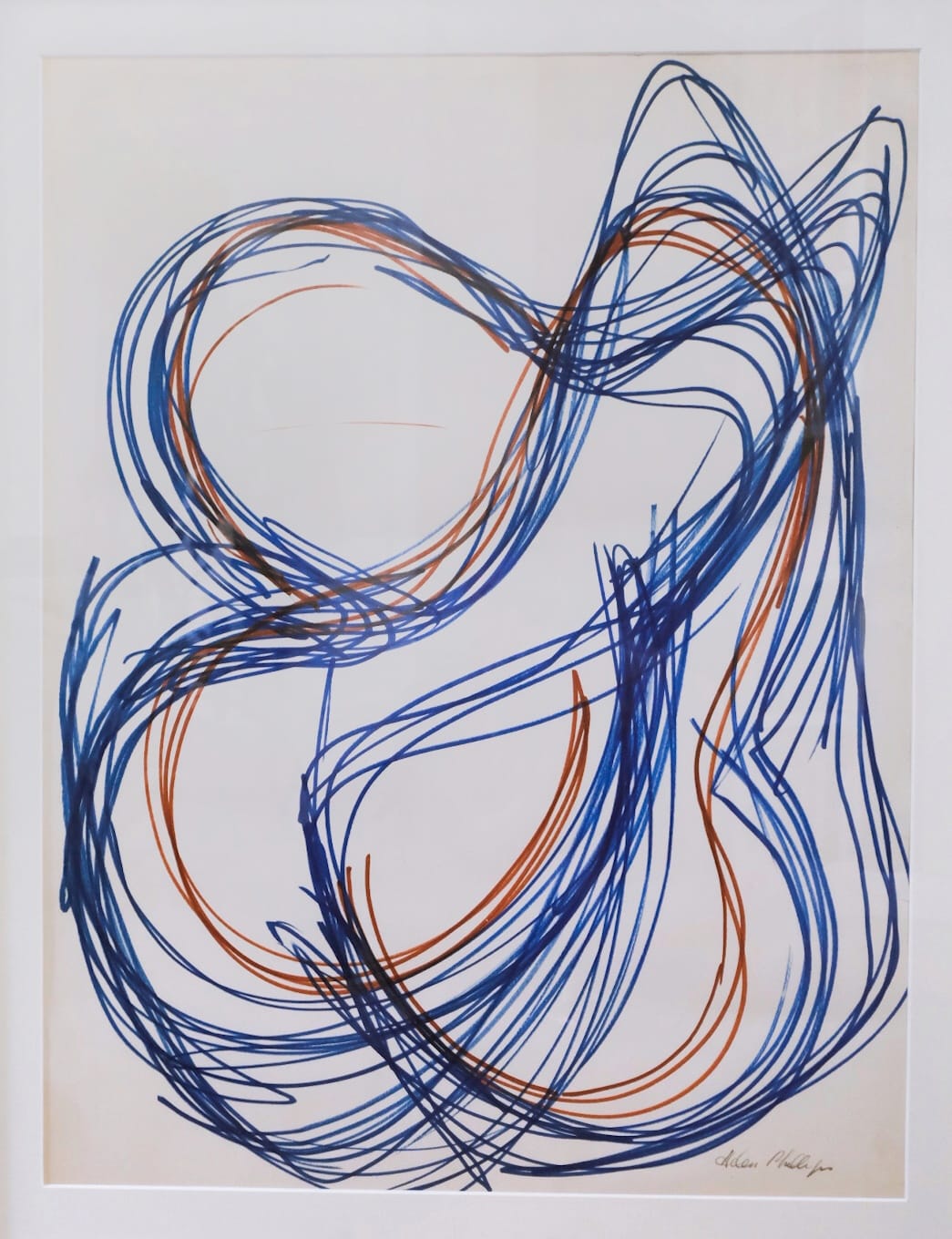

Perhaps the most well-documented development of Phillips’ career was her exploration of a Module of Growth during the 1960s. Thomson’s concepts of recurring patterns and modular compositions can be seen in Phillips’s many versions of Growth (Croissance), both on paper and in metal. Using Thompson’s approach of repetitions and natural geometries, Phillips created highly variable chains and columns, some symmetrical and some asymmetrical. Phillips also studied the principles of modularity as in the writings of Buckminster Fuller to further her vision for angular kinetic compositions.

As her experimental sculptures in aluminium rods had proven to be too fragile to be cast in bronze, in the late 60s Phillips started using copper wire covered with wax and had a selection of her sculptures cast in bronze, in the lost wax method.

Latest period: New York and Paris

1972 – 1995

In 1967 Phillips severely injured her back while moving a large stone sculpture, which the Albright Knox Art Gallery in Buffalo, New York (now AKG Art Museum), had recently purchased. The sculpture, Alabaster Column (1966), currently lists in the museum collection as Forme abstraite (Abstract Form).

Her injury affected her ability to sculpt for several years. Undeterred, she continued to create with the same vigour and dedication, even if on a more intimate and manageable scale. Continuing her explorations in modular, universal growth and geometric unity, Phillips created a significant late body of works far removed from her earlier images. She replaced her ambiguous poetic image with well defined geometric structures; used lightweight wire as an inky pen drawing through space, and created new forms that relate more to science than to the precolonial art, or to the Surreal imagery of her earlier works.

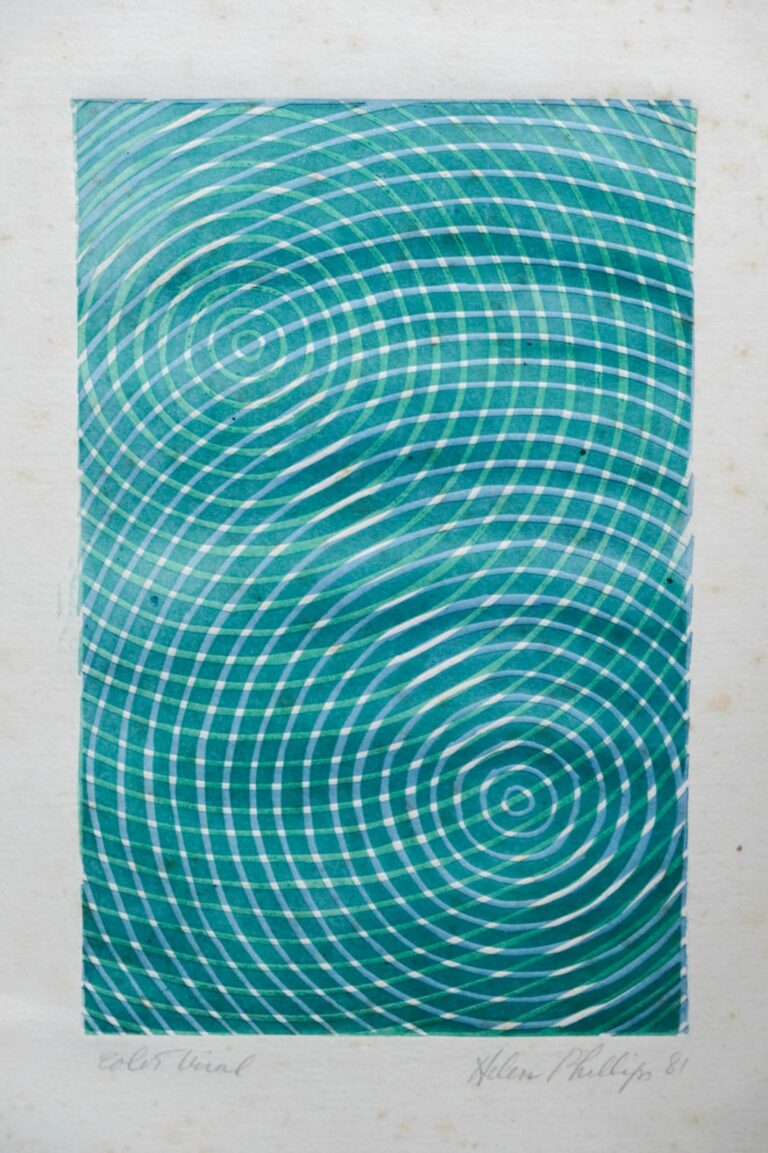

Her graphic works always reflected what was going on in her sculptures. When the physically demanding technique of engraving into copper or zinc became too challenging, she pivoted to creating relief prints in linoleum. She took great care carving repetitive linear patterns in an abstract and minimal style, reflecting her interest in wave theory, refracted light, and the Fibonacci sequence (golden ratio). In fact her prints from the 1970s and 1980s, have the effects of light as their main subjects. In these late years Phillips enhanced her production with series of metallic geometric constructions using iron rods, assembling hundreds of models in iron wires, wax, and cardboard. She created large sets of aluminum square tubes for 15-foot-high sculptures, which she referred to as drawings in space.

In 1972, she experienced a deeply painful divorce from Hayter, her companion of 36 years. This led to isolation from mutual friends and a detachment from the art world she had been a part of until then. With characteristic determination, she resumed working on her sculptures and prints almost in solitary. She granted few interviews, wrote about Atelier 17, and provided insightful accounts of her own art. Fully aware of her significance as a powerful figure of her time, she also served as an indispensable witness to the world she inhabited, leaving behind valuable writings. She spent her last twenty years alternating between her atelier in Greenwich Village, New York, and the one in rue Boissonade in Paris. In the summer months she frequented the foundries of Pietra Santa, Italy, completing earlier projects and beginning new works. She continued to explore new ways of creating until her death in 1995.

Helen Phillips Biography

Early life and the Beginnings

1931 – 1936

Helen Elizabeth Phillips was born in Fresno in 1913. She came from a family descending from the first german settlers on the West Coast. Her father was a violin teacher and the other members of her family were artistically and intellectually inclined: her sister Ruth became an art gallerist and her other sister an anthropologist.

From about the age of thirteen, Phillips knew she wanted to be a sculptor, always finding ways to carve; she would use wood, soap, or even lumps of dry earth she found in vineyards during the dry season. By fifteen, while living with her family in San Francisco, she took a summer sculpture class at the California School of Fine Arts (now the San Francisco Art Institute).

After high school, she returned to study with sculptors Ralph Stackpole and Gottardo Piazzoni from 1932 to 1935.

During this time, she met Diego Rivera, a close friend of Stackpole, who had recently completed commissions for the San Francisco Stock Exchange and the California School of Fine Arts. It was not Rivera’s masterful mural painting that most impressed Phillips, but his renowned collection of pre-Columbian artifacts and Mexican sculptures. These, along with the University Museum’s collection of Indigenous American, Chinese, and Aztec arts and her growing interest in the poetry of the early Surrealist writers, and in their psychoanalytic techniques shaped Phillips’s sculptural ideals.

Paris and Atelier 17

1936 – 1939

In 1936, after winning the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art Purchase Prize for her sculpture Young Woman (1935–36) and completing a private sculpture commission for Saint Joseph Catholic Church in Sacramento, CA, she was awarded a Phelan Traveling Fellowship to study abroad.

She traveled throughout Austria, Germany, Italy, and France, eventually settling down in Paris to a little room on the Impasse de Rouet. Soon carving sculptures outdoors became impracticable because of the dropping temperatures. She instead joined friends at Atelier 17, the intaglio print workshop of the renowned English artist Stanley William Hayter, whom she would later marry.

A hub of avant-garde experimentation, the atelier transcended generational and stylistic divisions, gathering together artists who subsequently endorsed different movements. Among its attendees were Pablo Picasso, Max Ernst, Alberto Giacometti, Joan Miró, André Masson, Jean Hélion, Maria Helena Vieira da Silva, Gabor Peterdi, and Nina Negri, to name a few.

In those early Parisian years, she produced approximately thirty-five copper plates, almost all representing images inspired by the Surrealist practice of “automatic writing”, aimed at freeing the unconscious. Driven by her interest in pure form, she sought to achieve what she later called the ambiguous poetic image, combining abstract content with the ambiguity of Surrealist concepts.

London and the World War II

1939 – 1940

As the political situation worsened in Europe and another war seemed imminent, Phillips and Hayter, who had been openly living together since 1937, left for London in 1939, as Hayter was called to serve his country.

Due to Hayter’s political stance and commitment (he had produced two portfolios in aid of the Spanish Republic and housed Spanish refugees), there was an urgency for the couple to flee France before German forces invaded. Both artists were forced to abandon most of their works in Paris. Later, Peggy Guggenheim was able to retrieve some of their work (including Hayter’s important painting Parturition, 1939), but most Phillips’s sculptures were lost and, so far, none has been recovered.

The couple began working with Roland Penrose, Ernö Goldfinger, and Julian Trevelyan in the Industrial Camouflage Research Unit, where artists helped civilian businesses and factories use camouflage to defend themselves against air raids.The Unit, based in Goldfinger’s offices, consisted of leading figures in the English Surrealist Group. During these nerve-racking months, Phillips kept sculpting any way she could, while also making prints at Julian Trevelyan’s studio at Durham Wharf. Apart from Trevelyan, Hayter and Phillips’s close circle of friends included John Buckland-Wright, Anthony Gross, Lee Miller, and Roland Penrose. During this time Phillips became close to Ërno and Ursula Goldfinger. In 1940, the Industrial Camouflage Research Unit, having been dismantled, Phillips and Hayter decided to leave Europe for the United States.

The New York Years

1940 – 1950

Due to immigration issues, Hayter left in an Allied convoy from Liverpool to a Canadian port, arriving in NewYork via train. Phillips, then pregnant with their first son, left England on one of the last American refugee boats for New York.

They stayed for a week with Gordon Onslow Ford before leaving for San Francisco, where Hayter had a summer teaching position lined up at the California School of Fine Arts. On their way to California, Phillips and Hayter were married in Reno, Nevada. Their first child was born at the end of August, seven weeks prematurely. Once the summer session was over, Hayter returned to New York, where he had been invited to teach and reestablish his Atelier 17 at the New School for Social Research. Phillips joined him with their infant son at the beginning of December. They moved into a two-bedroom apartment on 14th Street and Seventh Avenue. It was spacious, but still did not have enough room for them to work. Due to Augy’s health issues, they left New York and spent the first two years on the East Coast in Connecticut. They then moved to New York City, from where Hayter would continue to commute.

“This proved nearly disastrous for us, both morally and financially, because of the isolation from our kind of people, which was essential for our lifestyle.” (from Phillips’s unpublished papers)

By early1943, they went back to New York, first to Perry Street, then to Waverly Place. Having moved constantly since leaving Paris, there they found for the next four years the stability they needed. Despite being overwhelmed with work and responsibilities, their strong constitutions made these years prolific and vital for both artists, crucial for their aesthetics.

Within just a few years of arriving in New York, Phillips made a name for herself; her reputation as a sculpture set her on par with the leading Surrealist and Abstract Expressionists of the time. Besides being published in the prestigious avant-garde art magazine Tiger’s Eye, her work was included in many significant exhibitions. In 1941, her hieratic sculpture Inverted Head (1941) was included in Surrealism, an exhibition organized by Roberto Matta at the New School for Social Research. In 1945, she displayed her carved limestone sculpture Genetrix (1943) in the second Women exhibition at Peggy Guggenheim’s Art of This Century Gallery. In 1947 she was represented by her sculptures Moto Perpetuo and Dualism (both 1944–45) in the landmark exhibition Bloodflames, curated by Nicholas Calas, at New York’s Hugo Gallery. Included in the exhibition were some of the most significant representatives of Surrealism and Abstract Expressionism: Isamu Noguchi, Roberto Matta, David Hare, Wilfredo Lam, Arshile Gorky, and Jeanne Reynal.

By this time, Phillips was creating medium-sized sculptures expanding her range of techniques and materials, which included bronze (which she polished herself), stone, balsa wood, plaster, iron, and aluminum wire tubes. Most of these works reflected her personal surrealist vocabulary of abstract forms.

When Phillips and Hayter moved into the brownstone on Waverly Place, in 1944, they could finally afford the space for their professional, social, and family needs. Phillips settled her sculpture studio in the old dining room at the front of the building and began again to cut stone in the backyard, while Hayter used an upstairs room for his painting and drawing. The large kitchen became a frequent gathering place for their friends—among them Marc Chagall, Jacques Lipchitz, André Masson, and Joan Miró—to exchange ideas about art.

In 1949 Phillips and Hayter were featured in Sidney Janis’s 1949 exhibition Artists: Man and Wife, which paired artist couples: Elaine and Willem de Kooning, Lee Krasner and Jackson Pollock, Barbara Hepworth and Ben Nicholson, and Sophie Taeuber-Arp and Jean Arp. Clement Greenberg’s assessment of the show offered qualified praise for Phillips at the expense of the other women artists represented:“Helen Phillips was the only woman whose work equaled that of the man.” Interestingly, the backwards compliment reflects the broader critical perception of the time that women artists were in a subordinate position to men.

Phillips, Atelier 17 and the “Surrealists in Exile”

By then mother of two young children, Phillips could rarely go to Atelier 17 and work on her prints.

She later remembered that when she did, she would place her second child Julian’s cradle under the press for protection. However, she was “intimately involved with all that was going on at the Atelier through Bill (as Hayter was called) and the artists who would come by their house.”

In several recorded interviews and unpublished writings, Phillips provided a detailed account of her lifestyle with Hayter, their means of production at the time, and of her household, where many “Europeans in exile” and American artists would gather to discuss what would later become history.

“Until we moved to Waverly Place, I could only note ideas in small plasters and engrave a few plates on the fringe of Bill’s workspace and domestic demands. Finally at Waverly Place I could begin to cut stone again in the outdoor yard. From my study on the basement ground I could at the same time keep an eye on our small children, who were fed, bathed and put to bed by seven, leaving me free, after supper, to concentrate on my work…and Bill could could go to the shop until midnight for classes or projects he was on and go to a pub with his crowd afterwards at the Cedar Tree or the White Horse Tavern…it was in the dining room off the very big kitchen which also housed Julian’s playpen, a sofa, a very big dining table and chairs around, that our personal friends and particularly our house guests… gathered for a coffee and art-idea discussions. This room was the hub of our household. Beside Ruthven (Todd) I particularly remember Chagall, who, badly grieving for his wife’s death, found consolation there, Lipchitz, Masson, Becker, Miró on very frequent occasions…People coming to our front door were taken directly to the top floor, to Bill’s studio or down to the kitchen, en famille…”

Helen Phillips and S.W. Hayter: an artistic complicity

“There is a fourth dimension to the marriage of working artists…there is marriage…you have children, and when your professions are the same, and you understand so much of so much, it gives another dimension to the marriage. Some people see it as a negative but there is a very very positive side to it…”

By the late 1940s, Phillips and Hayter had managed to buy a brownstone house on Washington Street in the West Village, where they shared a large atelier in the basement. By then, they had developed a deep artistic bond, sharing interests, a vision, and exploring new directions in their art.

Phillips recalls their enthusiasm in discussing Thompson Darcy’s theories of modular growth and how they relied on each other’s judgment to advance when their work stalled. Their mutual understanding was intuitive; they instantly grasped where the other’s work was headed. Coming from different artistic backgrounds, their insights into each other’s work were unconditioned, and had a complementary quality that benefited both. Phillips’s admiration for Hayter never faltered, and Hayter constantly supported her art. He always included her prints in his Atelier 17 exhibitions, illustrated them in his books, and often sketched from her works.

By 1949, Phillips’ work had gained such prominence within the circle of leading American avant-garde sculptors that she was invited to join the prestigious Eighth Street Club. Its members included Mark Rothko, Robert Motherwell, William Baziotes, Isamu Noguchi, and David Hare.

However, she reluctantly had to decline this prestigious offer as Hayter was adamant about returning to Paris for a couple of years. Those two years turned eventually into an indefinite period.

Later, in an interview with David Cohen, Phillips admitted she regretted returning to Paris.

“For some reason Bill [Hayter] wouldn’t play with it at all. I never understood it. It would have made a great difference to me because that group (the Eight Street Club) supported me, morally, as a sculptor.”

Return to Paris

The 1950s through 1970s

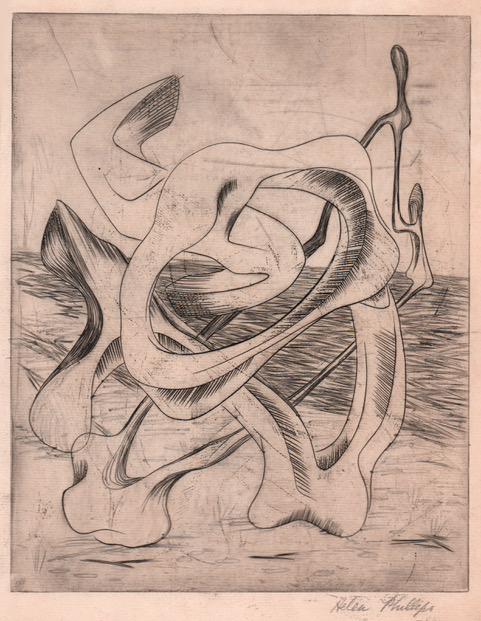

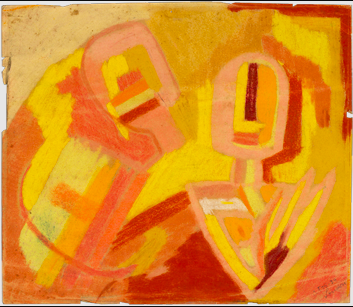

In the early summer of 1950, after the Hayters returned to France, Phillips was invited by André Chanson, director of the Petit Palais, to showcase fourteen sculptures in the exhibition New York Six, and thereafter was invited to exhibit in numerous European international Biennials and Salons. In the late fall of 1950 Hayter reopened Atelier 17 and Helen started to frequent it again. Over the following four years, abandoning her black and white engravings, she developed her own method of making bold colour prints, using deep bite and simultaneous colour printing.

In the 1950s the French poet André Lothe, called for artists and intellectuals to settle in the houses and ruins of Alba-la-Romaine, an idyllic medieval town in the Ardèche region of southern France. Lothe’s article, which appeared in the Parisian newspaper Combat, made the rounds in the cafés of Montparnasse, and many artists of the Paris School decided to leave the postwar struggles of the city for the charm and serenity of Alba. Artists of all nationalities purchased and settled in about thirty houses there, establishing an international art scene in an otherwise quiet, provincial town. Phillips and Hayter were among those who joined this artists’ community: in 1953 the couple purchased an old stone house where they had adjoining studios. They would spend most of their summers there with their children, finding fulfillment and inspiration in nature and a simpler way of life.

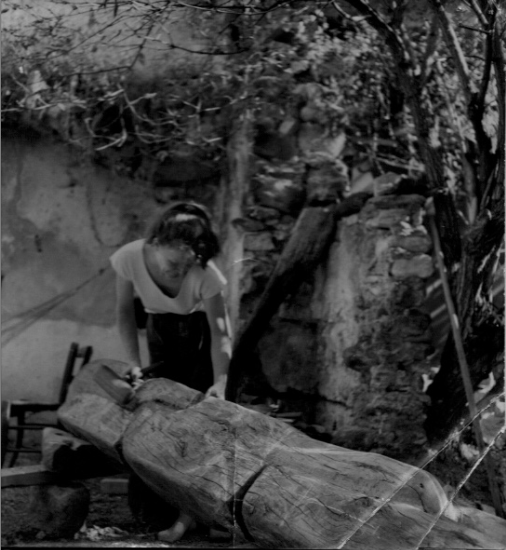

In Alba, Phillips began carving 300–400 year old oak trees found nearby and created multiple large-scale totems, one titled Family Totem (1953), reaching a height of seventeen feet. She continued to work in her ambiguous poetic image style, which was strongly influenced by her interest in ethnographic arts, merging human forms with the natural world. A pair of totem-like figures titled Eve (1958) and Adam (1960) were purchased by the Dallas Museum of Art in 1960.

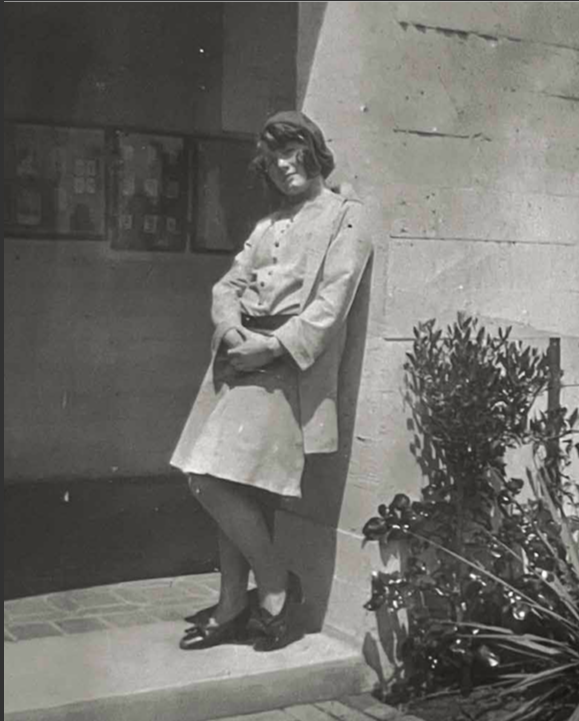

In 1956, at Ërno Goldfinger’s invitation, Phillips participated in the breakthrough exhibition This Is Tomorrow at the Whitechapel Gallery in London, with a hanging sculpture carved from balsa wood titled Suspended Figure (1956). The original piece, purchased by Goldfinger, is now lost, but a cast in aluminum survives in the Goldfinger residence, at 2 Willow Road in London, with a photographic documentation of the artist posing next to the original. Goldfinger noted in a letter to Victor Pasmore (17 July1956) that “Helen Phillips stayed with me for some 10 days and finished her piece of sculpture at my house…it is in balsa wood and I think rather good…She made a most hellish dust over the whole house when sandpapering it; everything is covered with a thin layer of balsa dust!”

Many of Phillips’s sculptures from this time were exhibited in Paris at the Musée Rodin, Salon de Mai, Galerie Pierre, Galerie La Hune, Galerie Claude Bernard, and consistently throughout Europe where she was often called to represent the United States. In 1962 she took part in the exhibition, 14 Americans in France, which, initiated by the American Cultural Center in Paris, travelled all over the United States.

A Module of Growth

“It was not until 1954 when I read D’Arcy Thompson’s inspiring volumes on growth and form that I evolved a geometric unit to express three-dimensional movement which in repetition, produced a seemingly endless variety of forms, column spirals in geometric relationship and developed from a single given length: A Module of Growth.”

Perhaps the most well-documented development of Phillips’ career was her exploration of a Module of Growth during the 1960s. Thomson’s concepts of recurring patterns and modular compositions can be seen in Phillips’s many versions of Growth (Croissance), both on paper and in metal. Using Thompson’s approach of repetitions and natural geometries, Phillips created highly variable chains and columns, some symmetrical and some asymmetrical. Phillips also studied the principles of modularity as in the writings of Buckminster Fuller to further her vision for angular kinetic compositions.

As her experimental sculptures in aluminium rods had proven to be too fragile to be cast in bronze, in the late 60s Phillips started using copper wire covered with wax and had a selection of her sculptures cast in bronze, in the lost wax method.

Latest period: New York and Paris

1972 – 1995

In 1967 Phillips severely injured her back while moving a large stone sculpture, which the Albright Knox Art Gallery in Buffalo, New York (now AKG Art Museum), had recently purchased. The sculpture, Alabaster Column (1966), currently lists in the museum collection as Forme abstraite (Abstract Form).

Her injury affected her ability to sculpt for several years. Undeterred, she continued to create with the same vigour and dedication, even if on a more intimate and manageable scale. Continuing her explorations in modular, universal growth and geometric unity, Phillips created a significant late body of works far removed from her earlier images. She replaced her ambiguous poetic image with well defined geometric structures; used lightweight wire as an inky pen drawing through space, and created new forms that relate more to science than to the precolonial art, or to the Surreal imagery of her earlier works.

Her graphic works always reflected what was going on in her sculptures. When the physically demanding technique of engraving into copper or zinc became too challenging, she pivoted to creating relief prints in linoleum. She took great care carving repetitive linear patterns in an abstract and minimal style, reflecting her interest in wave theory, refracted light, and the Fibonacci sequence (golden ratio). In fact her prints from the 1970s and 1980s, have the effects of light as their main subjects. In these late years Phillips enhanced her production with series of metallic geometric constructions using iron rods, assembling hundreds of models in iron wires, wax, and cardboard. She created large sets of aluminum square tubes for 15-foot-high sculptures, which she referred to as drawings in space.

In 1972, she experienced a deeply painful divorce from Hayter, her companion of 36 years. This led to isolation from mutual friends and a detachment from the art world she had been a part of until then. With characteristic determination, she resumed working on her sculptures and prints almost in solitary. She granted few interviews, wrote about Atelier 17, and provided insightful accounts of her own art. Fully aware of her significance as a powerful figure of her time, she also served as an indispensable witness to the world she inhabited, leaving behind valuable writings. She spent her last twenty years alternating between her atelier in Greenwich Village, New York, and the one in rue Boissonade in Paris. In the summer months she frequented the foundries of Pietra Santa, Italy, completing earlier projects and beginning new works. She continued to explore new ways of creating until her death in 1995.

Helen Phillips Chronology

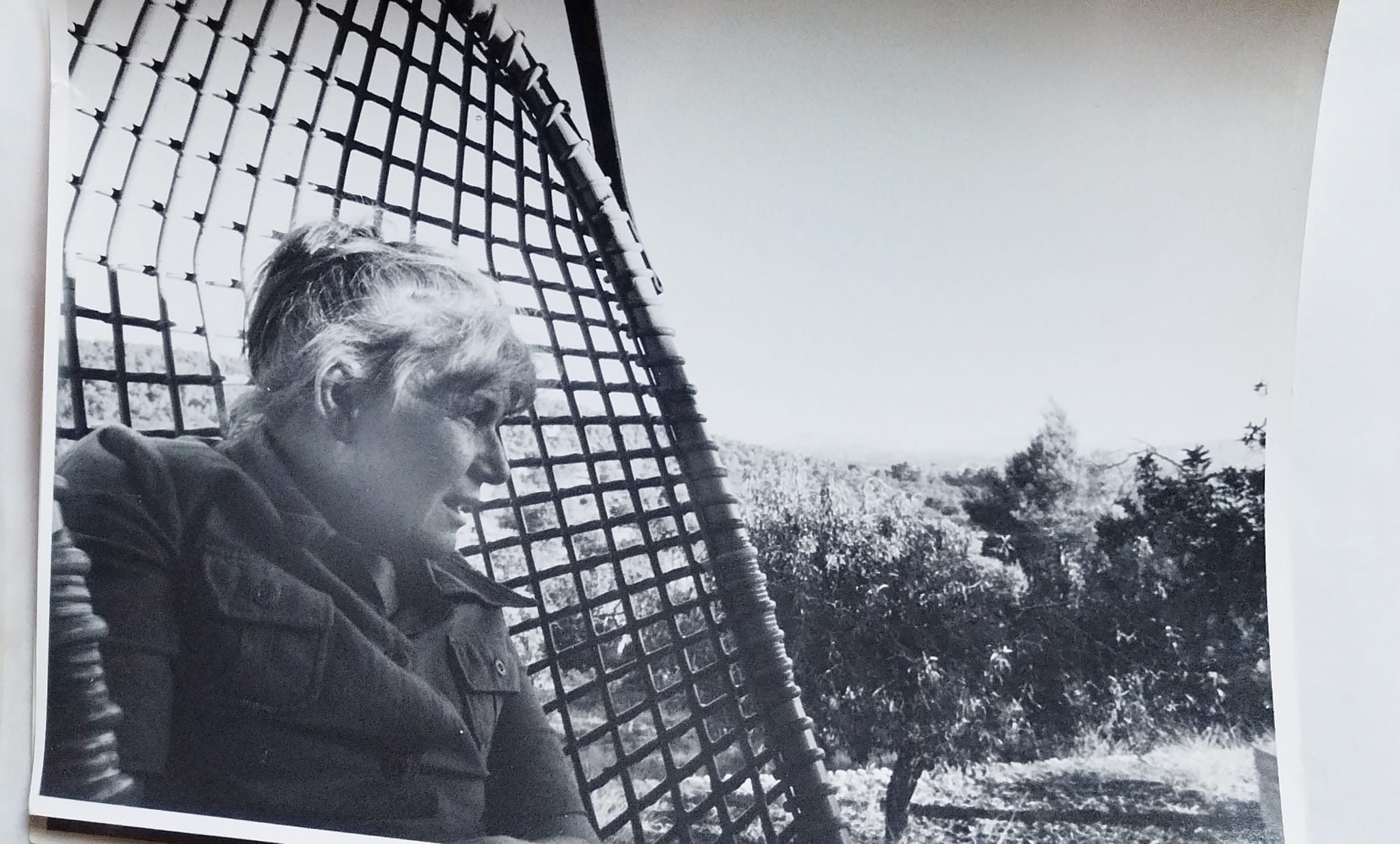

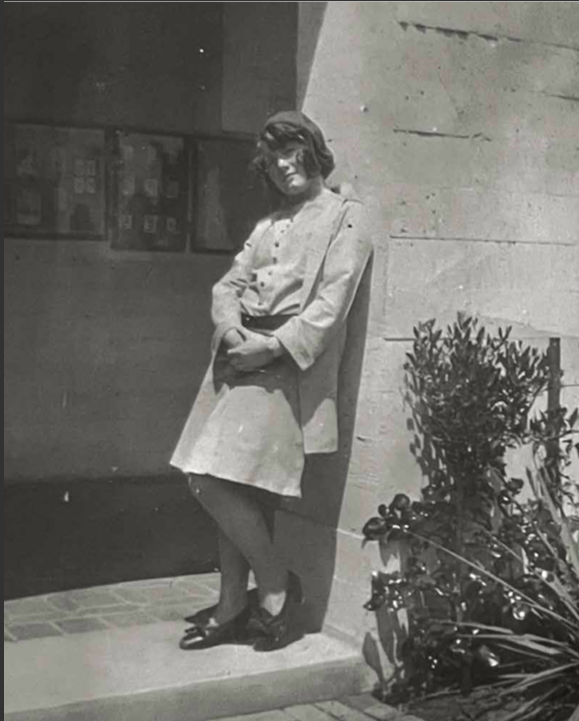

Helen Phillips, late 20s, San Francisco

Helen with her friends at Yellow Pine Beach, Yosemite 1930

The Flutist blowing a horn and Chinese player, 1937-1938, Treasure Island.

Untitled IV, pastel on paper, London, October 1939

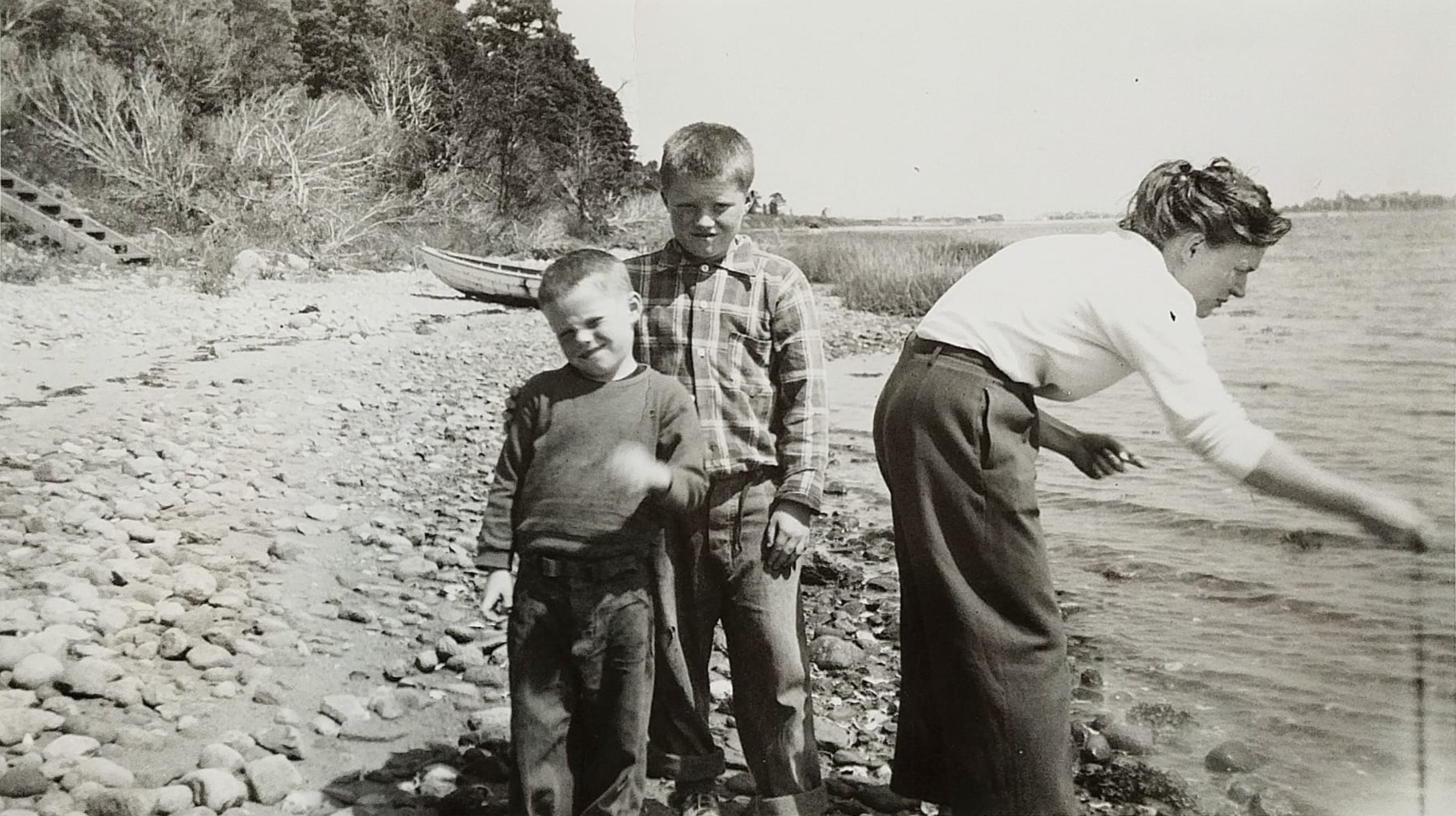

Helen with her sons, late 40’s.

Helen standing next to her bronze sculpture Dualism.

Helen, Bill Hayter and sons in Alba.

Helen standing next to her balsa wood sculpture Jeux de Jambes II, 1956.

Helen Phillips working on Eve.

Adam and Eve, Dallas Museum of Art

Wire Sculpture, 1974.

Cosmos III, 1976. Soft ground etching and simultaneous color printing.

Helen Phillips “drawing in space”, 1990s drawing in pastels colors

1913

Born March 12 in Fresno, California

1928

Attends summer sessions at the California School of Fine Arts.

1932 – 1935

Studies under Ralph Stackpole at the California School of Fine Arts. Develop an interest in Amerindian, Chinese and Aztec arts from university museum collections and Diego Rivera’s personal collection of Mexican Art.

1936

Awarded the San Francisco Museum Purchase Prize for her stone carving Young Woman, 1935, which becomes part of SFMOMA’s permanent collection.

Receives a Phelan Traveling scholarship funded by the San Francisco Art Association; travels throughout Italy and France and establishes herself in Paris.

Attends Stanley William Hayter’s experimental print workshop at 17 rue Campagne-Première in Paris.

1937

Returns to San Francisco for six months for a commission for three figural sculptures flanking a major fountain at the Golden Gate International Exhibition held in Treasure Island, in the San Francisco Bay.

1938

Her sculptures for the fountain are represented at the International Exhibition in San Francisco. At the same time she takes a position teaching at the CSFA.

1939

Back in Paris she starts working directly in plaster and develops her own personal language of forms, which she describes as ambiguous poetic Image: a mixture derived from nature, people and animals. Begins to explore the multiple interplay of relationships when opening a solid volume, making the empty spaces as equally concrete of the solid mass. In contrast to her stable objects she develops ideas for a flow of asymmetric movement in space.

Due to the imminence of the war, Phillips and Hayter leave Paris for London. The dire war conditions of London limits her art production. So far only two pastels of that period, testimony of her explorations in colour, have been retrieved.

1940

Leaves London for New York, where the couple reunites. They are welcomed and hosted by Gordon Onslow Ford. They travel by train from New York to San Francisco, where they arrive on June 8th. On the way, they stop in Reno, Nevada, to get married. Gives birth to their first child, Augy. Exhibits at the San Francisco Museum of Art. Preceded by Hayter, who goes to New York in October to re-establish his Atelier 17 and find lodging for his family, Phillips and their child move there in December.

1941

Her sculpture Inverted Head – Portrait is included in the Surrealist Show organized by Matta at the New School for Social Research.

1943

Birth of their second child, Julian Thomas, at Greenwich Hospital in New York.

1944

Phillips’ marble carving Genetrix, 1943, is illustrated in Carola Gideon-Walker’s “Contemporary Sculpture” and included in the exhibition “31 Women” at Peggy Gugghenheim’s Art of this Century Gallery, New York.

1947

Phillips’ bronze sculptures Moto Perpetuo, 1946, and Dualism, c.1945, are included in the groundbreaking exhibition “BloodFlames” curated by Nicolas Calas at the Hugo Gallery, New York.

Wins the Edgar Walter Sculpture Prize.

Participates in the Annual Exhibition of the Art Institute of Chicago, focused for the first time on Abstract and Surrealist trends.

1948

Wins the Timothy Pflueger Sculpture Prize.

Exhibits at the Whitney Museum, NYC.

Moto Perpetuo, 1946, is exhibited at the Chicago Art Institute 58th Annual Exhibition of American Painting and Sculpture.

1949

Phillips and Hayter in the Sidney Janis Gallery exhibition “Artists: Man and Wife”.

1950 – 1975

Returns to Paris and exhibits regularly for the following 25 years at the Galerie Pierre, Galerie La Hune, the American Embassy in Paris and the American Cultural Center.

Exposes yearly at Salon de Mai, Salon de la Jeune Sculpture Contemporaine et Salon de Réalités Nouvelles.

1953

Begins direct carving in ancient oak in Alba where she and Hayter bought a house.

Wins the French Prize in the International Sculpture Competition for the Unknown Political Prisoner at the Tate Gallery with her bronze Metamorphose II, 1952-53.

Exhibits at the Biennale, Antwerp and at Galerie Martinet, Amsterdam.

1956

Her sculpture Jeux de Jambes II, 1956, is included in the exhibition “This is Tomorrow – collaborations of Architect, Sculptor, Painter” in tandem with Erno Goldfinger at the Whitechapel Gallery in London.

Exhibition “Prints by Stanley William Hayter and Helen Phillips” at the Achenbach Foundation, Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco.

1960

Her sculpture Adam and Eve on view at the Salon de Mai in Paris, is acquired by the Dallas Museum of Art.

1967

Injures her back while moving the large Alabaster Column just acquired by the Albright Knox Fort Museum, Buffalo. Her ability to sculpt is compromised for a few years. She gradually turns to lighter materials and new techniques in printmaking.

1969

Her prints and sculptures exhibited at Art and Architecture, University of California, Horizon Northwest, Salem.

1972

Phillips and Hayter divorce.

1970 – 1994

Produces drawings, modular wire sculptures and experiments with large scale color lithography and linocuts.

Travels regularly between her studios in Montparnasse, Paris and New York.

1988

Is the subject of a documentary by the BBC “American Sculptor Helen Phillips, Paris Studio.”

1994

Dies in Greenwich Village, NYC. English art critic David Cohen dedicates a full half-page obituary to her in “The Independent”, London.

She leaves behind a body of nearly 400 known sculptures and 80 prints, and a vast quantity of drawings.

2023

Christa Story’s book “Form, Growth and Variation” is edited by the Wright Museum of art.

2023

The association Helen Phillips Archives is established in Paris.

1913

Born March 12 in Fresno, California

1928

Attends summer sessions at the California School of Fine Arts.

1932 – 1935

Studies under Ralph Stackpole at the California School of Fine Arts. Develop an interest in Amerindian, Chinese and Aztec arts from university museum collections and Diego Rivera’s personal collection of Mexican Art.

1936

Awarded the San Francisco Museum Purchase Prize for her stone carving Young Woman, 1935, which becomes part of SFMOMA’s permanent collection.

Receives a Phelan Traveling scholarship funded by the San Francisco Art Association; travels throughout Italy and France and establishes herself in Paris.

Attends Stanley William Hayter’s experimental print workshop at 17 rue Campagne-Première in Paris.

1937

Returns to San Francisco for six months for a commission for three figural sculptures flanking a major fountain at the Golden Gate International Exhibition held in Treasure Island, in the San Francisco Bay.

1938

Her sculptures for the fountain are represented at the International Exhibition in San Francisco. At the same time she takes a position teaching at the CSFA.

1939

Back in Paris she starts working directly in plaster and develops her own personal language of forms, which she describes as ambiguous poetic Image: a mixture derived from nature, people and animals. Begins to explore the multiple interplay of relationships when opening a solid volume, making the empty spaces as equally concrete of the solid mass. In contrast to her stable objects she develops ideas for a flow of asymmetric movement in space.

Due to the imminence of the war, Phillips and Hayter leave Paris for London. The dire war conditions of London limits her art production. So far only two pastels of that period, testimony of her explorations in colour, have been retrieved.

1940

Leaves London for New York, where the couple reunites. They are welcomed and hosted by Gordon Onslow Ford. They travel by train from New York to San Francisco, where they arrive on June 8th. On the way, they stop in Reno, Nevada, to get married. Gives birth to their first child, Augy. Exhibits at the San Francisco Museum of Art. Preceded by Hayter, who goes to New York in October to re-establish his Atelier 17 and find lodging for his family, Phillips and their child move there in December.

1941

Her sculpture Inverted Head – Portrait is included in the Surrealist Show organized by Matta at the New School for Social Research.

1943

Birth of their second child, Julian Thomas, at Greenwich Hospital in New York.

1944

Phillips’ marble carving Genetrix, 1943, is illustrated in Carola Gideon-Walker’s “Contemporary Sculpture” and included in the exhibition “31 Women” at Peggy Gugghenheim’s Art of this Century Gallery, New York.

1947

Phillips’ bronze sculptures Moto Perpetuo, 1946, and Dualism, c.1945, are included in the groundbreaking exhibition “BloodFlames” curated by Nicolas Calas at the Hugo Gallery, New York.

Wins the Edgar Walter Sculpture Prize.

Participates in the Annual Exhibition of the Art Institute of Chicago, focused for the first time on Abstract and Surrealist trends.

1948

Wins the Timothy Pflueger Sculpture Prize.

Exhibits at the Whitney Museum, NYC.

Moto Perpetuo, 1946, is exhibited at the Chicago Art Institute 58th Annual Exhibition of American Painting and Sculpture.

1949

Phillips and Hayter in the Sidney Janis Gallery exhibition “Artists: Man and Wife”.

1950 – 1975

Returns to Paris and exhibits regularly for the following 25 years at the Galerie Pierre, Galerie La Hune, the American Embassy in Paris and the American Cultural Center.

Exposes yearly at Salon de Mai, Salon de la Jeune Sculpture Contemporaine et Salon de Réalités Nouvelles.

1953

Begins direct carving in ancient oak in Alba where she and Hayter bought a house.

Wins the French Prize in the International Sculpture Competition for the Unknown Political Prisoner at the Tate Gallery with her bronze Metamorphose II, 1952-53.

Exhibits at the Biennale, Antwerp and at Galerie Martinet, Amsterdam.

1956

Her sculpture Jeux de Jambes II, 1956, is included in the exhibition “This is Tomorrow – collaborations of Architect, Sculptor, Painter” in tandem with Erno Goldfinger at the Whitechapel Gallery in London.

Exhibition “Prints by Stanley William Hayter and Helen Phillips” at the Achenbach Foundation, Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco.

1960

Her sculpture Adam and Eve on view at the Salon de Mai in Paris, is acquired by the Dallas Museum of Art.

1967

Injures her back while moving the large Alabaster Column just acquired by the Albright Knox Fort Museum, Buffalo. Her ability to sculpt is compromised for a few years. She gradually turns to lighter materials and new techniques in printmaking.

1969

Her prints and sculptures exhibited at Art and Architecture, University of California, Horizon Northwest, Salem.

1972

Phillips and Hayter divorce.

1970 – 1994

Produces drawings, modular wire sculptures and experiments with large scale color lithography and linocuts.

Travels regularly between her studios in Montparnasse, Paris and New York.

1988

Is the subject of a documentary by the BBC “American Sculptor Helen Phillips, Paris Studio.”

1994

Dies in Greenwich Village, NYC. English art critic David Cohen dedicates a full half-page obituary to her in “The Independent”, London.

She leaves behind a body of nearly 400 known sculptures and 80 prints, and a vast quantity of drawings.

2023

Christa Story’s book “Form, Growth and Variation” is edited by the Wright Museum of art.

2023

The association Helen Phillips Archives is established in Paris.

Helen Phillips’ Awards

1936

San Francisco Museum of Art

Sculpture Prize

1936

Phelan Traveling Fellowship

1947

Edgar Walter

Sculpture Prize

1948

Timothy Pflüger Sculpture Prize

San Francisco Museum of Art

1952

Unknown Politician Prisoner

International Competition : French Prize

1958

Copley Foundation Sculpture Prize

(International Award)