Sculptor – Printmaker

Helen Phillips’

Artworks

Helen Phillips’ Artworks

“My first métier …was always sculpture.

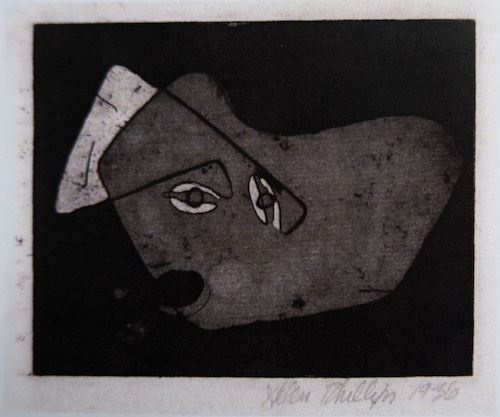

My second métier was engraving which is closely allied with sculpture. I learned all of the current black-and-white techniques when, as a sculptor, I first joined the Atelier 17 in 1936 and preferred straight engraving because of its close association to sculpture.” Helen Phillips

From the very first burin practices at Atelier 17, Phillips’s sculptures and prints have always been in communication, both physically and visually. Printmaking allowed Phillips a quicker experimentation and less commitment than sculpture. Understanding the positive and negative aspects of the printmaking process made her aware of the vitality of the line also in sculpture and gave her a new freedom in understanding the meaning of ‘abstract’.

Phillips’s production counts about 80 known prints, over 400 known sculptures and a vast quantity of drawings.

Selected Works

Sculptures

“My concepts have always been adapted to the nature of the material I worked in directly. It has been essential to me to dominate but never destroy the quality of the material as it contains its own particular vitality.”

In her writings, Helen Phillips described her sculptures as falling into five main categories: Stone Carving | Polished Bronze | Woodcarving | Pure Geometrical and Linear Sculptures

Stone

Wood

Bronze

Linear

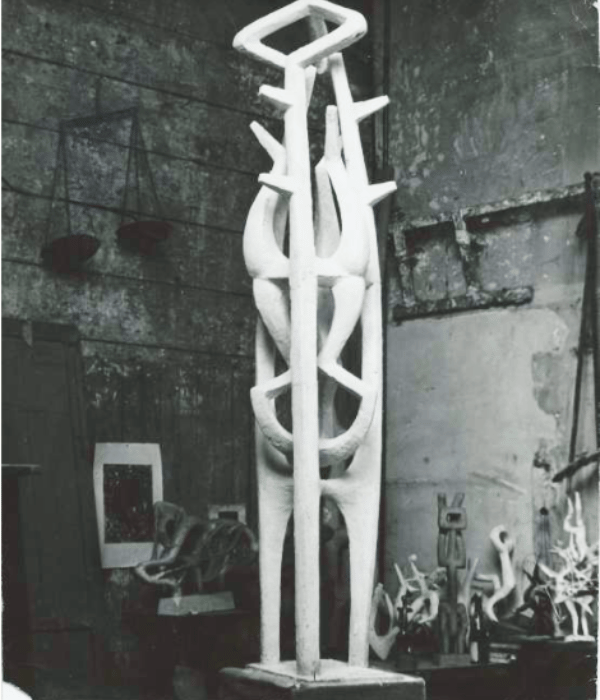

Plaster

Prints

(Helen Phillips’ Memoirs)

1930s – 1940s

1950s – 1960s

1970s – 1980s

Critical Essays: extracts

Nicholas Calas, 1947 - Bloodflames

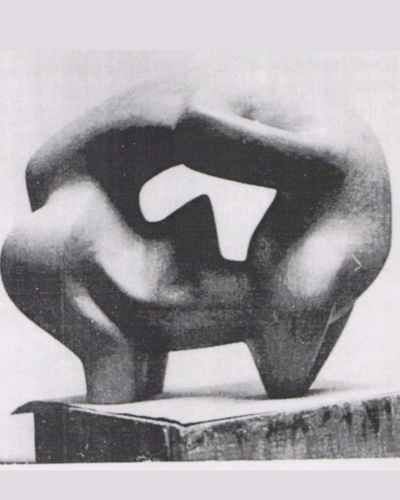

When motion is viewed in terms of a timeless present, the union between male and female is no longer felt as a fulfilment but as an emptiness that remains un-overcome despite the efforts of the sexes to melt their bodies into one entity.

Translated into the language of forms this poetic theme is best expressed through the use of inner spaces.

The inner space is a mirror of emptiness reflecting those movements which are in conflict and which confront each other as asymmetric opposites. While in Henry Moore the inner space remains a pit absorbing man’s soul and compelling him to recline over his grave, in the bronzes of Helen Phillips it spreads out like a lake upon which one yearns to sail beyond oneself – despite the fact that one is doomed never to lose sight of the coast of existence.

Because Helen Phillips’ statues grow around emptiness they look like cross- sections of infinity or spheres of eternity. To the stillness of the body of an archaic statue that defies space, she opposes the stillness of an emptiness that defies bodily movements; to the symmetry of form of a classical sculpture she opposes the inevitable asymmetry of complementary surfaces.

Helen Phillips’ preoccupation is with the void rather than with infinity. Instead of stretching toward the gothic unseen, she concentrates on circumscribing emptiness. Yet her statues are objects, concrete things rather than merely symbols of a post aesthetic reality. Although Helen Phillips’ statues are not “ abstract” they are not “literary” because her mode of expression is not expansive.

Hers, is essentially a hermetic sculpture.

Roland Penrose, Paris 1958

Jeu d’Oracle, Paris, février 1958

Bois, pierre et métal hébergent, chacun selon sa nature, la sensibilité, l’émotion , et

les pensées de Helen Phillips.

Du bois elle sait reconnaitre la vie antérieure, l’élan, les gestes et les entorses que sa lutte avec le destin a provoqués. La volonté de l’artiste adopte joyeusement les contraintes imposées au hasard par la nature. Elle les accepte comme un défi et en les épousant leur infuse un avenir fertile.

De même la pierre exige d’être comprise et, de nouveau, le sculpteur écoutant ses secrets l’engage dans une conversation grave pleine des échos préhistoriques.

Obéissant au feu, le métal accepte de laisser couler dans ses nervures les idées libres et durables. Le jeu s’équilibre. Dans un dressage rigoureux, la dompteuse apprend à son éleve de bronze des numéros savants. Ses membres devenus antenne d’un organisme puissant tracent la solution invisible et véritable de nos angoisses et de nos désires.

Dites-moi si c’est dans la main même, solide et sensible, ou dans sa fille, l’empreinte dans l’espace, que nous lisons l’avenir au même titre que nous comprenons le passé?

Michel Seuphor, The Sculpture of this Century, New York 1960

…..The work of Helen Phillips is characterised by power and

suppleness at the same time. She sometimes expresses herself through Helen Phillips, Moon, bronze, 1960 a massive and heratic immobility, sometimes through a moving yet solid

spatiality. Her work inspires an almost metaphysical confidence and

security, even to the dance figures that she commits to bronze ….

…. bois et bronzes d’un rythme souple joint à une stricte discipline

Carola Giedon-Welcker, Contemporary Sculpture, 1961

…in Helen Phillips’ work (one can feel)… those dominating, irrational and primeval forces whose ritual sense has been lost in our time…

Herbert Read, A Concise History of Modern Sculpture

…Scorn and criticism are justified when nothing new is added to the old image…

But if the antique idea is given a new, precise, original image, then there is no cliché, as in Helen Phillips‘ imaginative vision of Moon, 1960

David Cohen, The Independent, London, 1994

From Helen Phillips’ Obituary

The Independent, London, 1994

…

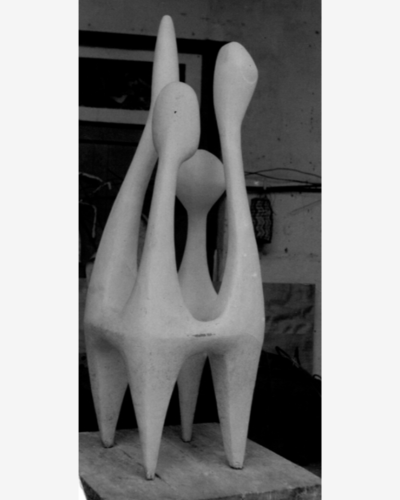

Such mythic qualities identify Helen Phillips as a sculptural pioneer within the emerging NewYork School and indeed she showed in Niclolas Calas landmark exhibition Bloodflames 1947…..had she not returned to Paris in 1950 she would have developed a considerable American reputation. Meanwhile the primitive influence culminated in the 18 foot, Totem, 1955

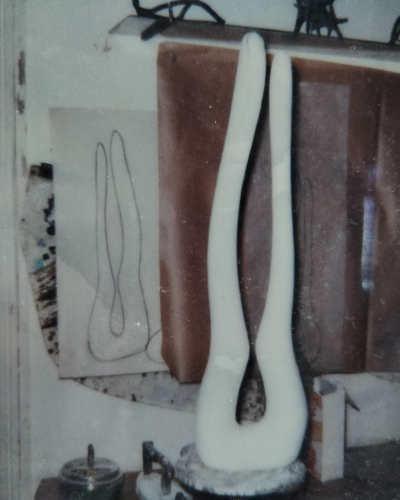

…Phillips was by first inclination a carver: she only started using bronze by chance, when one of her wood carvings split and she wanted to save the image. She soon found herself absorbed by a more linear range of expression suggested by metal, however, and her figures in copper tubing are delightful Calder-like figures in space. Her compositions in polished bronze exploit light with almost baroque intensity to give the maximum sensation of mouvement and gesture. Amants Novices, 1954 is a masterpiece in this genre….The conflicting sense of precarious balance and vigorous abandon captures the magical clumsiness of sex.

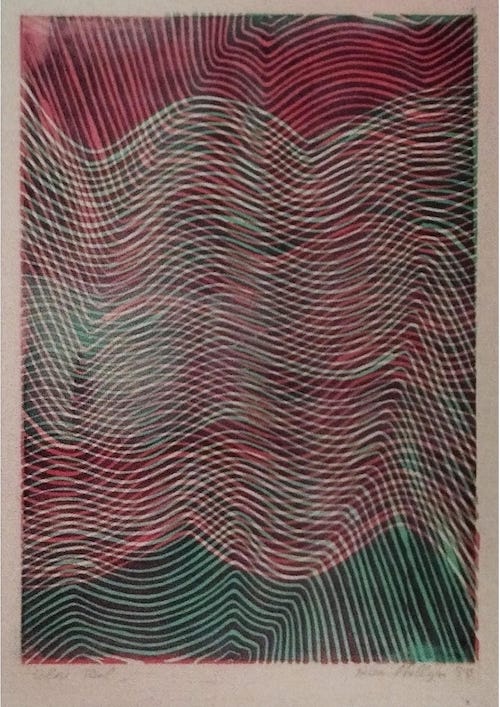

In a completely different vein Phillips produced an extensive series of geometric constructions in wire which explored ideas of modular growth proposed by the American architectural theorist Buckminster Fuller, and also by Sir Wentworth D’Arcy Thompson whose “ Growth and Form” , 1917/1942, has been a bible for many modern artists. Phillips recalls how she worked out of one volume, her husband Bill Hayter from the other, so they would have interesting things to talk about. Hayter’s wave imagery derived from Thompson, while Phillips pursued a complicated set of cubic abstractions to express mouvement in space. ….

Until the 60s Helen Phillips enjoyed a growing international reputation, starting with a prize she won in the French heat of the international “Unknown Political Prisoner” competition, in 1952. She collaborated with Erno Goldfinger, who owned her Suspended Figure, 1956, which was included in the Whitechapel Gallery’s “This is Tomorrow “ exhibition of that year. She was cited by Herbert Read definitive survey “Modern Sculpture”, 1964, and her works began to enter important collections, including those of Peggy Guggenheim, Roland Penrose, and various American Museums.

…(In her late years) She concentrated on seeing earlier ideas through the foundry, and became a familiar figure in Pietra Santa, the town of foundry and carving workshops in Tuscany, during the summer months. She produced some late intimate pieces in wire, plaster and wax; some years ago she sent her friend an eccentric Christmas card, which consisted of a DIY model in balsa wood which, when constructed, showed a couple embracing. Man Ray was so delighted that he sent her a photo of the assembled sculpture by return of post. Another endearing tale she used to tell was of a party attended by Calder and Giacometti. Giacometti made a sketch of Calder on a piece of old newsprint (paper table cloth, CE). The American demanded to see it and proceeded to sketch Giacometti next to his own feature.They were about to throw it away when Phillips protested and got to keep these mutual portrait of her friends and idols.

Terri Geis, Blog, September 7, 2010

June in Paris with the Surrealists with forms in perpetual motion and transformation.

For the past year, I have been working as a research assistant here at LACMA, helping the curator Ilene Susan Fort with the preparations for a major exhibition called In Wonderland: the Surrealist Adventures of Women Artists in Mexico and the United States.

This show, opening in January of 2012, will showcase the work of many well-known artists such as Frida Kahlo, but also introduce many important women who have not achieved such international renown. One of the most enjoyable aspects of working on this project has been tracking down key paintings and sculptures by these lesser-known artists and learning about their extraordinary lives.

This past June, I was lucky enough to travel to Paris in the pursuit of information on one such artist, Helen Phillips. ….

In Paris I went to stay with Phillips’ daughter-in-law, the Italian curator Carla Esposito Hayter, whose apartment in Saint-Germain-des-Prés is right down the street from the famous Café Les Deux Magots.

With regular doses of espresso and pain au chocolat, we spent long hours happily digging through Phillips’ documents from throughout her career, including wonderful photographs such as this of Phillips and Hayter in their studio.

We also measured and photographed many examples of Phillips’ work, lugging bronze sculptures onto a bathroom scale (it is important to have a weight estimate for shipping purposes).

Phillip’s best-known sculpture is a work in Carla’s apartment called Metamorphose (1946) a good example of the artist’s concern with forms in perpetual motion and transformation.

As Carla and I were looking with forms in perpetual motion and transformation.

Through a batch of old photographs of Phillips’ sculptures, she suddenly realized that one of the works was in corner of the bedroom where I was staying. Neither she nor I had given much attention to the piece, which seemed sort of flat and nondescript. However, as we carried the bronze out into the living room and set it in the proper position according to the old photograph, a fully-realized work came to life.

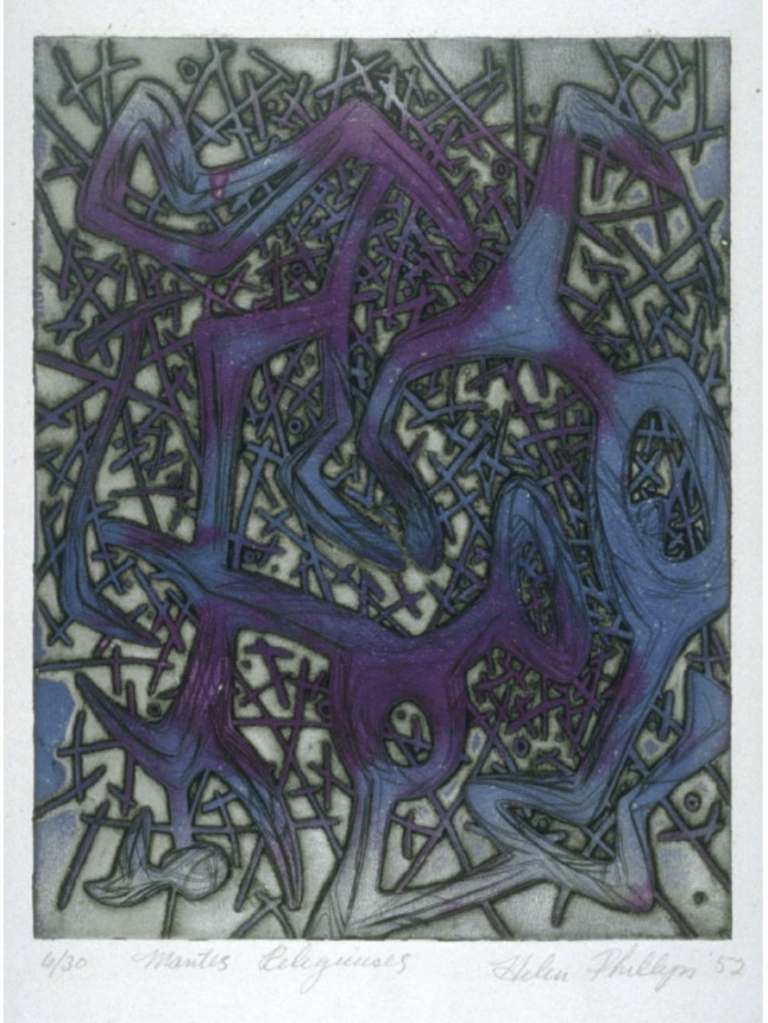

Although the piece is romantically called Amants Novices (Inexperienced Lovers), its sharp “teeth” and tangled limbs give the sculpture a slightly menacing quality that may relate to the surrealist interest in symbols of violent female sexuality, such as the Praying Mantis.

Carla and I were very excited about our discovery, and it may turn out that this sculpture is perfect for a show about the ways in which women artists responded to surrealist concepts.

Christina Weyl, Woman's Art Journal, Spring 2018

Shifting Focus,Women printmakers at Atelier 17, Woman’s Art Journal, Spring 2018

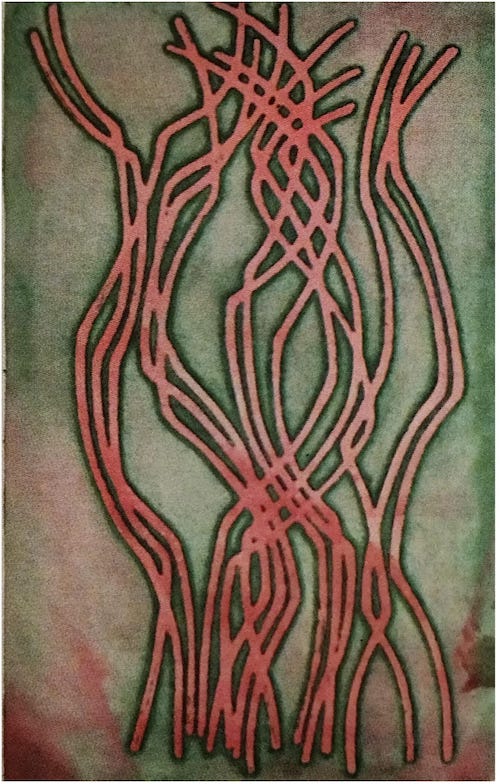

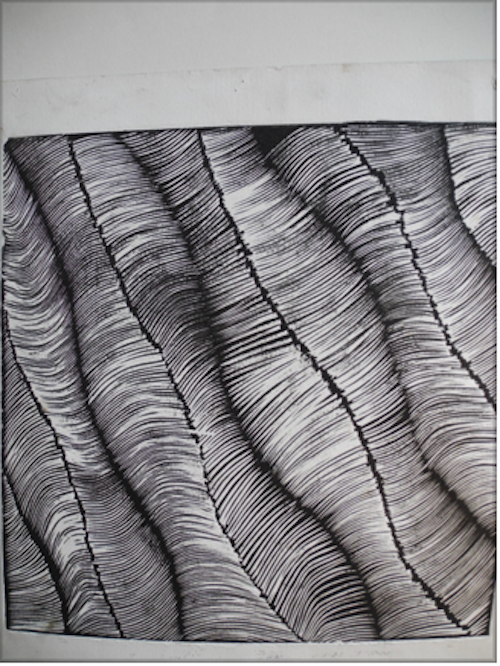

The experience of incising copper with the burin sharpened her (Helen Phillips) understanding of positive and negative space, and altered the way she dealt with sculptural volume.

Looking at the trajectory of her sculpture, it would appear that engraving altered her sensibility, leading her to open up the forms of her early, blocky direct carving and to develop sinus, twisting limbs in her later cast and polished bronze works.

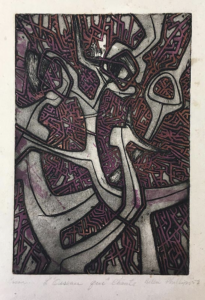

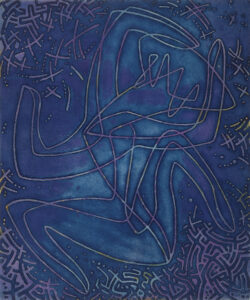

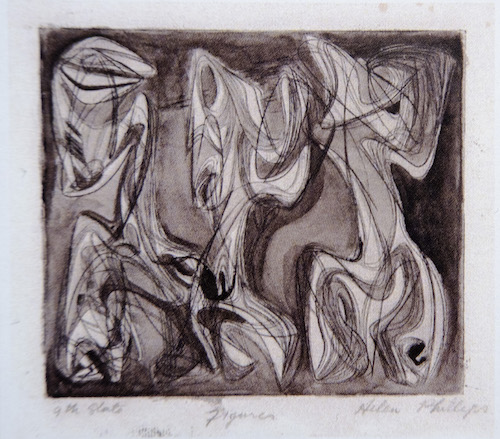

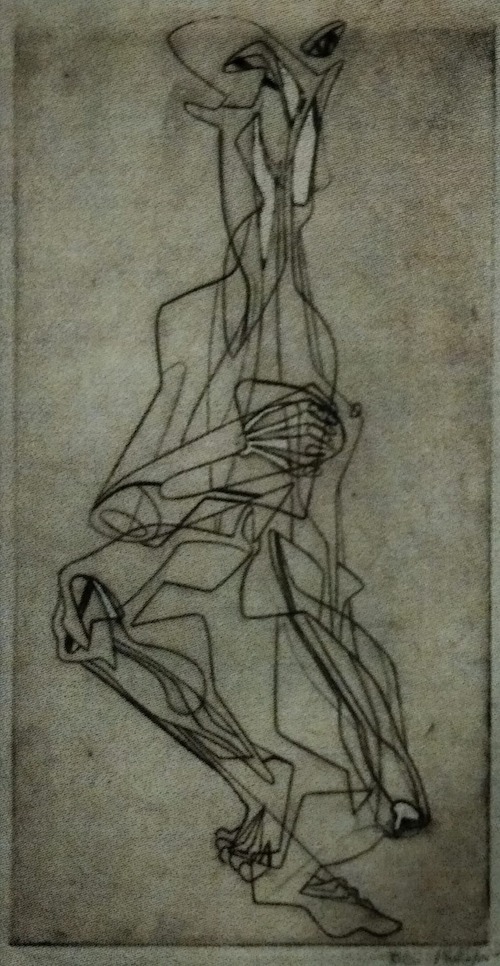

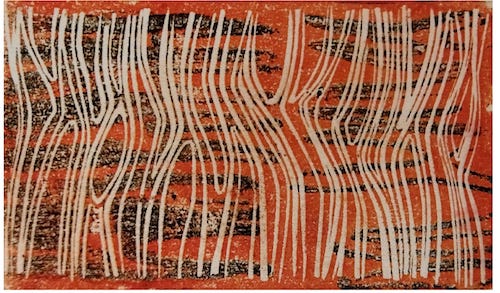

One of her first intaglio plates figures a headless sticky figure, a recurring form that she described as “two joint wishbones” amid swirling drypoint lines that suggest motion and even dance, which was a motif that would occupy her when she returned to printmaking in the 1950s after a decade- long child-raising hiatus.

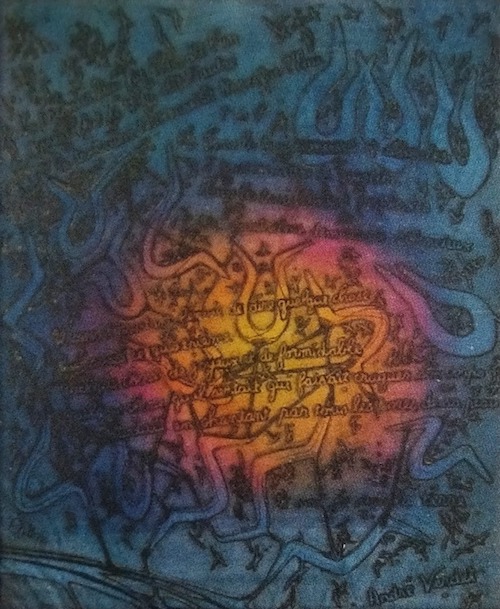

Her 1950s prints are deeply sculptural and brilliantly model simultanées colour printmaking, one of Atelier 17 signatures techniques…

Giulia Smith, London 2019

Helen Phillips: Biography and Future Directions, Londres 2019

Today, few know about Phillips.

This lack of recognition is particular harrowing as she enjoyed international recognition at the start of her career. During her lifetime, her work entered the collections of Peggy Guggenheim and Roland Penrose, along with those of MOMA, SF MOMA and the Smithsonian Museum of American Art.

Among her papers one finds dozens of press cuttings in praise of her sculptures and exhibitions, along with professional photographs portraying her works at various stages of completion. Clearly, Phillips kept this material because she recognised her worth and was set on preserving her legacy.

Given the level of gender discrimination in the art world of the 1930s– 50s, it seems extraordinary that her biography should be punctuated by a roster of prestigious fellowships, international awards and high-profile exhibitions.

Remarkably, Phillips participated in women-only shows as early as the 1940s, a time that is commonly regarded as a dormant hiatus in the history of feminist displays. This suggests that our understanding of this period in art history is not only rudimentary but deeply skewed by the interests of a market that subsequently favoured male artists.

Given her stature, it is imperative that Phillips is rescued from oblivion.There is no time better than the present to embark on this recovery mission.

In recent years, major exhibitions and scholarly publications have endeavoured to re-evaluate the work of twentieth-century women artists, as well as of West Coast modernists operating in a transnational context (think of Pacific Standard Time, 2013, and LA/LA, 2017, both led by the Getty Research Institute).

In 2017, the Terra Foundation for American Art and AWARE organized a conference on women-only exhibitions (‘WAS —Women Artists Shows, Salons, Societies: expositions collectives d’artistes femmes,

1876–1976’, 2017).

More recently, the Yale/Paul Mellon Centre for British Art founded a research project by Dr Giulia Smith on the work of the women in This Is Tomorrow (‘Women of Tomorrow’, 2018–ongoing).

Against this background, Helen Phillips may once again emerge as an extraordinarily ambitious sculptor and a central player in the transnational development of twentieth-century modernism.

Christina Weyl, Musée des Beaux Arts de Rennes, 2021

From Women of Atelier 17 and the sculptural potentials of print in “Hayter @ l’Atelier du Monde”, Musée de Beaux Arts de Rennes, 2021

….In June of 1936, twenty-three-year-old Phillips received a life-changing opportunity when the San Francisco Art Association selected the California-born sculptor for its inaugural Phelan Scholarship, given to a student of the California School of Fine Arts for travel abroad.

Local and national media outlets covered news of Phillips’s award and her plans for spending the $2,000 prize money, roughly the equivalent of $37,500 today.

Having studied direct carving with Robert Stackpole (1885-1973), she intended to further her work as a sculptor, beholding ancient wonders such as Mayan pyramids and Toltec temples in Mexico, modern architecture in Germany, and the great art collections of Italy and France.

Betraying the period’s insular focus on the “Americanness” of American art at this moment, Phillips explained “My hope is that through foreign travel I shall be able to achieve the dissociation of ideas necessary to view more clearly my own country and to determine the real sources of America from which a National art is to evolve.”

Phillips achieved dissociation abroad, but not in the way she had predicted. Finding it difficult to carve stone in her small lodging room, Phillips spent a few miserable weeks “making sentimental sketches” in Paris’ parks until she resolved to visit the city’s museums and strip herself of what she called the “social content school,” a reference to one of the prevailing aesthetic modes in the United States during the 1930s.

Along the way, she befriended several English-speaking artists —such as Edward Melcarth, Flora Blanc, and Dickson Reeder— who had all been working at Atelier 17 and encouraged Phillips to visit this experimental printmaking studio.

With her background in direct carving, Phillips related immediately to the process of incising copper plates with the engraver’s burin, a sharp diamond-shaped tool.

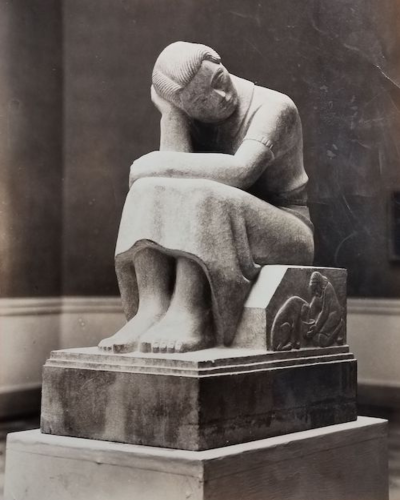

Yet Atelier 17 offered her more than technical mastery of another medium. As a meeting point for the city’s interwar Surrealist community, Atelier 17 introduced her to Surrealist artists and writers and Surrealist approaches to art making. The blocky, figural sculptures she had made in California—an example of which can be seen in a photograph of Phillips from 1935 — changed into biomorphic shapes, surreal scenes, and dream imagery. Although most of her sculpture from this time was lost —an unfortunate consequence of World War II—her Atelier 17 prints record this dramatic change.

Progressive state proofs for Sleep, for example, show Phillips developed the complex imagery by engraving the female head inside of an egg shape, and steadily built up the foetus-like anatomy, the onlooking heads, and shadowy surroundings.

(Phillips had also visited Brancusi’s studio, and the impression his work made is clearly evident.)

Atelier 17’s particular bent towards engraving— Hayter’s specialty— fostered robust connections with sculpture, attracting many curious sculptors to Atelier 17 and inspiring non-sculptors to begin their own experiments in three dimensions.

Although automatism was the guiding principle and Surrealism dominant during the studio’s first two decades, Hayter welcomed artists of all stylistic persuasion as long as they contributed to the studio’s mission of investigating the unknown and undiscovered through the graphic arts.

For Helen Phillips, engraving became a testing ground, prefiguring changes she would make in her sculpture. Carving into the plate spurred Phillips to open up solid volumes in her sculpture practice, making the voids “equally concrete as the solid mass.” The dramatic, sinuous and twisting forms she first imagined in an engraving of 1936, titled Sculpture on a Beach, foretell the plaster, marble, stone, and polished brass sculptures she executed from the 1940s until the 1960s such as Metamorphose and Amant Novices, which earned her a great deal of critical attention within the nascent New York School. (Hayter and Phillips lived in the United States from 1940 until 1950).

With two small children, she had less opportunity to leave the couple’s East Village brownstone and make prints at Atelier 17’s bustling New York studio spaces. However, she still worked diligently on sculptures in her studio (formerly the dining room.)

Engaging with Surrealist literary ideas, Phillips cultivated her own personal language, which she termed the “ambiguous poetic image.” Her work, she contended, was never abstract, but “a mix derived from nature of people/ animal/plant, permitting the onlooker’s interpretation.”

These organic forms often manifested as pared-down stick figures —a double wishbone, dancing or in contorted forms— in many prints and sculpture made in her heyday, roughly 1937 to 1967.

Phillips spoke in letters and statements about the universal power of her ambiguous forms.

In the early 1950s, Phillips created a bronze cast titled Metamorphose II in response to an international call from the Tate Gallery for a monument honouring political prisoners.

In a statement describing her submission, which won the competition’s French prize, Phillips explained that the figure is in transition —bound but striving for “free-flying movement”— and likened it to the mythical creature Pegasus or the god Prometheus, who was chained after giving fire to mortals. With their “constant and living insistence on freedom,” political prisoners are perpetually struggling against bindings both literal and metaphorical.

The symbiosis between Phillips’s Surrealist prints and sculpture reached its peak with her deeply bitten colour prints produced in Paris in the 1950s. With her children old enough to attend primary school, Phillips finally had the time to immerge herself again in printmaking and participate actively in Atelier 17’s bustling postwar workshop. Executed using viscosity printmaking (also called simultaneous colour printmaking), a signature technique that Atelier 17 members perfected in the mid-1940s for works like Hayter’s Cinq Personnages (1946), Phillips’s Pyramide (1950) and Naiades (1954) reflect a tangle of semi-abstract, dancing bodies which had become so fully realised in her sculptures. She further experimented with printing her plates in different colour combinations, which often alters the mood of the resulting work.

Augy Hayter's recollection

“My mother had left her family in California, my father had severed his relationship with his in England. During my childhood in New York, throughout the 40’s my family was who gravitated around the Atelier 17 and who, during their years in exile because of the war in Europe had constituted a strong hub around the old surrealists like my father.

It was a veritable crucible of contemporary art which had formed itself at the Atelier 17.

Personalities already well affirmed as Tanguy, Chagall, Masson, Liptchitz ou Max Ernst worked their engravings sitting in benches next to young people like Bob Motherwell, Milton Gendel, Jackson Pollock, Matta, Gorky, Baziotes, Rothko and de Kooning, just to mention the stars.”

Collections

Museum & Collections

San Francisco Museum of Art

Achenbach Collection, Palace Legion of Honor, San Francisco

Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Dallas Museum of Contemporary Sculpture

Albright-Knox, Buffalo, New York

Fine Arts Museum, Boston

Cleveland Museum.

Palmer Museum

Library of Philadelphia

Cincinnati Art Museum

Bank of America

Peggy Guggenheim Foundation, Venice (bronze later stolen from the collection)

Lee Miller and Roland Penrose Collection, Farleys House, England

Ernö Goldfinger’s Residence, England

Montague Bank, Bruxelles

Smithsonian, Washington

San Diego Museum

Library of Congress, Washington

The Elephant Trust (Roland Penrose and Lee Miller Foundation) Farley Farm, Sussex

Wright Museum, Beloit College, USA

Selected Exhibitions

1936-37/49/56/70 San Francisco Museum of Art

1942 New School of Social Research

1944 Museum of Modern Art, New York

1944 Art of this Century Gallery, New York

1947 Ian Hugo Gallery, New York

1948 Whitney Museum, New York

1949 Chicago Institute of Art

1949 Sidney Janis Gallery

1950/55 Petit Palais, Paris

1953 Tate Gallery, London

1953 Biennale, Middelheim, Belgium

1954 Palais de Beaux Arts, Bruxelles, Belgium

1956/65 Musee Rodin, Paris

1956 Whitechapel, London

1957 Musée d’art Moderne, Zurich

1961 Musée Rodin, Paris

1961/62 Smithsonian Museum, Washington D.C. and other museum venues in USA

1996 Guild Hall Museum, East Hampton, New York

2012/13 LACMA, Los Angeles and Museo de Arte Moderno, Mexico City

2021 Musée de Beaux Arts, Rennes

2023 Wright Museum, Beloit College, USA